Race Against Time in the Kernel’s Clockwork

An in-depth exploration of the Linux POSIX CPU Timer Subsystem, including patch analysis and vulnerability insights for Android Kernel CVE-2025-38352.

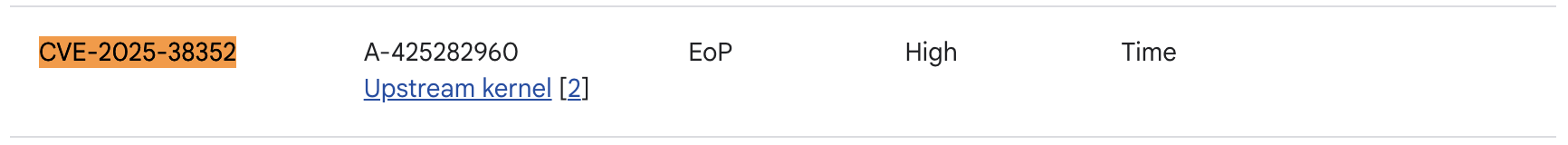

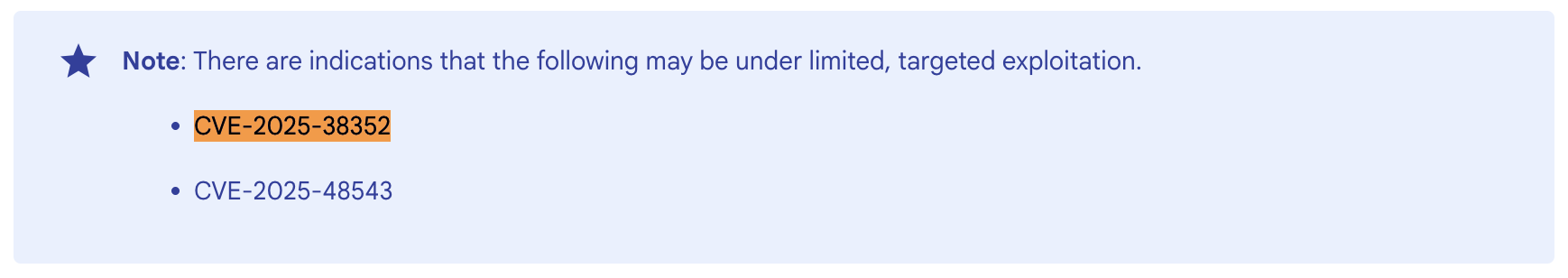

In this blog, I’ll be presenting my research on CVE-2025-38352 (a posix-cpu-timers TOCTOU Race Condition Bug) covering the patch-fix analysis, vulnerability analysis, and technical insights into my process of triggering the bug that caused a crash in the Android kernel. It was released in the September 2025 Android Bulletin, marked as possibly under limited, targeted exploitation.

DISCLAIMER: All content provided is for educational and research purposes only. All testing was conducted exclusively on an Android Kernel Emulator in a safe, isolated environment. No production systems or devices owned by the author or others were involved or affected during this research. The author assumes no responsibility for any misuse of the information presented or for any damages resulting from its application.

Overview

CVE-2025-38352 is a classic TOCTOU (Time-of-Check to Time-of-Use) vulnerability in the Linux/Android kernel’s Timer Subsystem. Specifically, it arises from a Race Condition in kernel/time/posix-cpu-timers.c. This flaw could lead to kernel instability, crashes, or unpredictable behavior, and in certain scenarios, may even be escalated into a privilege escalation on the target system.

We’ll begin with an in-depth exploration of the POSIX CPU Timer Subsystem and its internals, followed by a detailed patch and vulnerability analysis. Finally, we’ll walk through how this bug could be safely and reproducibly triggered in an isolated, emulated environment for demonstration purposes.

POSIX CPU Timer Internals

POSIX CPU timers represent a sophisticated timing mechanism in the Linux kernel that tracks actual processor usage rather than wall-clock time. Unlike traditional timers that measure elapsed real time, CPU timers monitor how much processing time tasks and processes actually consume, making them invaluable for profiling, resource management, and performance monitoring.

The Foundation: Three Types of CPU Time Measurement

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

static u64 cpu_clock_sample(const clockid_t clkid, struct task_struct *p)

{

u64 utime, stime;

if (clkid == CPUCLOCK_SCHED)

return task_sched_runtime(p);

task_cputime(p, &utime, &stime);

switch (clkid) {

case CPUCLOCK_PROF:

return utime + stime;

case CPUCLOCK_VIRT:

return utime;

default:

WARN_ON_ONCE(1);

}

return 0;

}

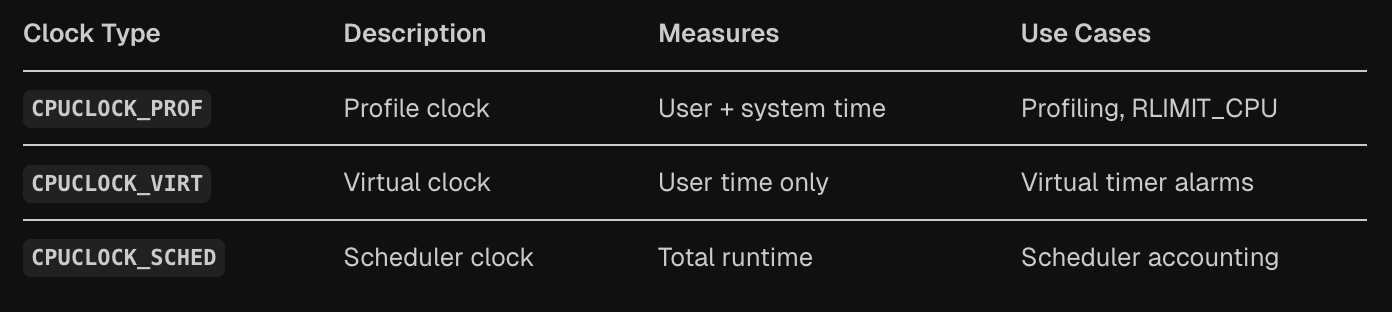

The system revolves around three distinct clock types seen in cpu_clock_sample, each serving different monitoring needs. The CPUCLOCK_PROF type measures combined user and system time, making it perfect for profiling applications and enforcing RLIMIT_CPU resource limits. The CPUCLOCK_VIRT type tracks only user-space execution time, useful for virtual timer alarms that shouldn’t count kernel overhead. Finally, CPUCLOCK_SCHED captures total scheduler runtime, providing the most comprehensive view of task execution.

Timer Creation and Management Infrastructure

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

static int posix_cpu_timer_create(struct k_itimer *new_timer)

{

static struct lock_class_key posix_cpu_timers_key;

struct pid *pid;

rcu_read_lock();

pid = pid_for_clock(new_timer->it_clock, false);

if (!pid) {

rcu_read_unlock();

return -EINVAL;

}

if (IS_ENABLED(CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK))

lockdep_set_class(&new_timer->it_lock, &posix_cpu_timers_key);

new_timer->kclock = &clock_posix_cpu;

timerqueue_init(&new_timer->it.cpu.node);

new_timer->it.cpu.pid = get_pid(pid);

rcu_read_unlock();

return 0;

}

...

...

static void arm_timer(struct k_itimer *timer, struct task_struct *p)

{

struct posix_cputimer_base *base = timer_base(timer, p);

struct cpu_timer *ctmr = &timer->it.cpu;

u64 newexp = cpu_timer_getexpires(ctmr);

if (!cpu_timer_enqueue(&base->tqhead, ctmr))

return;

if (newexp < base->nextevt)

base->nextevt = newexp;

if (CPUCLOCK_PERTHREAD(timer->it_clock))

tick_dep_set_task(p, TICK_DEP_BIT_POSIX_TIMER);

else

tick_dep_set_signal(p, TICK_DEP_BIT_POSIX_TIMER);

}

When applications create CPU timers, the kernel performs careful validation and initialization through the posix_cpu_timer_create function. This process validates the clock identifier, initializes timer queue nodes, and establishes the connection to the target process or thread. The system uses specialized lock classes for task work contexts to avoid false positive lockdep warnings, demonstrating the careful attention to kernel debugging infrastructure.

The kernel maintains timer state through a sophisticated queue system where active timers are organized in timer queues for efficient expiration checking. When timers are armed, the system updates expiration caches and sets tick dependencies to ensure the scheduler will check for timer expiration at appropriate intervals.

Fast Path Optimization for Performance

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

static inline bool fastpath_timer_check(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

struct posix_cputimers *pct = &tsk->posix_cputimers;

struct signal_struct *sig;

if (!expiry_cache_is_inactive(pct)) {

u64 samples[CPUCLOCK_MAX];

task_sample_cputime(tsk, samples);

if (task_cputimers_expired(samples, pct))

return true;

}

...

...

}

One of the most elegant aspects of the CPU timer system is its fast path checking mechanism, designed to minimize overhead during normal operation. The fastpath_timer_check function performs lock-free checks using cached expiration times, only triggering expensive timer processing when absolutely necessary. This optimization is crucial for system performance, as timer checks occur frequently during scheduler interrupts.

The fast path cleverly handles both thread-specific and process-wide timers, using atomic operations to read timer state without acquiring locks. This approach accepts occasional false negatives in exchange for dramatically reduced overhead, with the understanding that timer delivery delays are acceptable in practice.

Timer Expiration and Signal Delivery

When CPU timers actually expire, the system employs a sophisticated collection and firing mechanism. The collect_timerqueue function processes expired timers in batches, limiting the number processed at once to prevent excessive interrupt latency. Expired timers are marked as firing and moved to a temporary list for processing outside the critical timer queue locks.

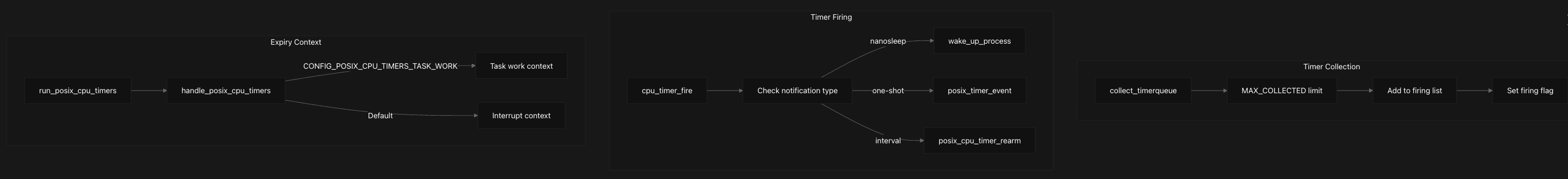

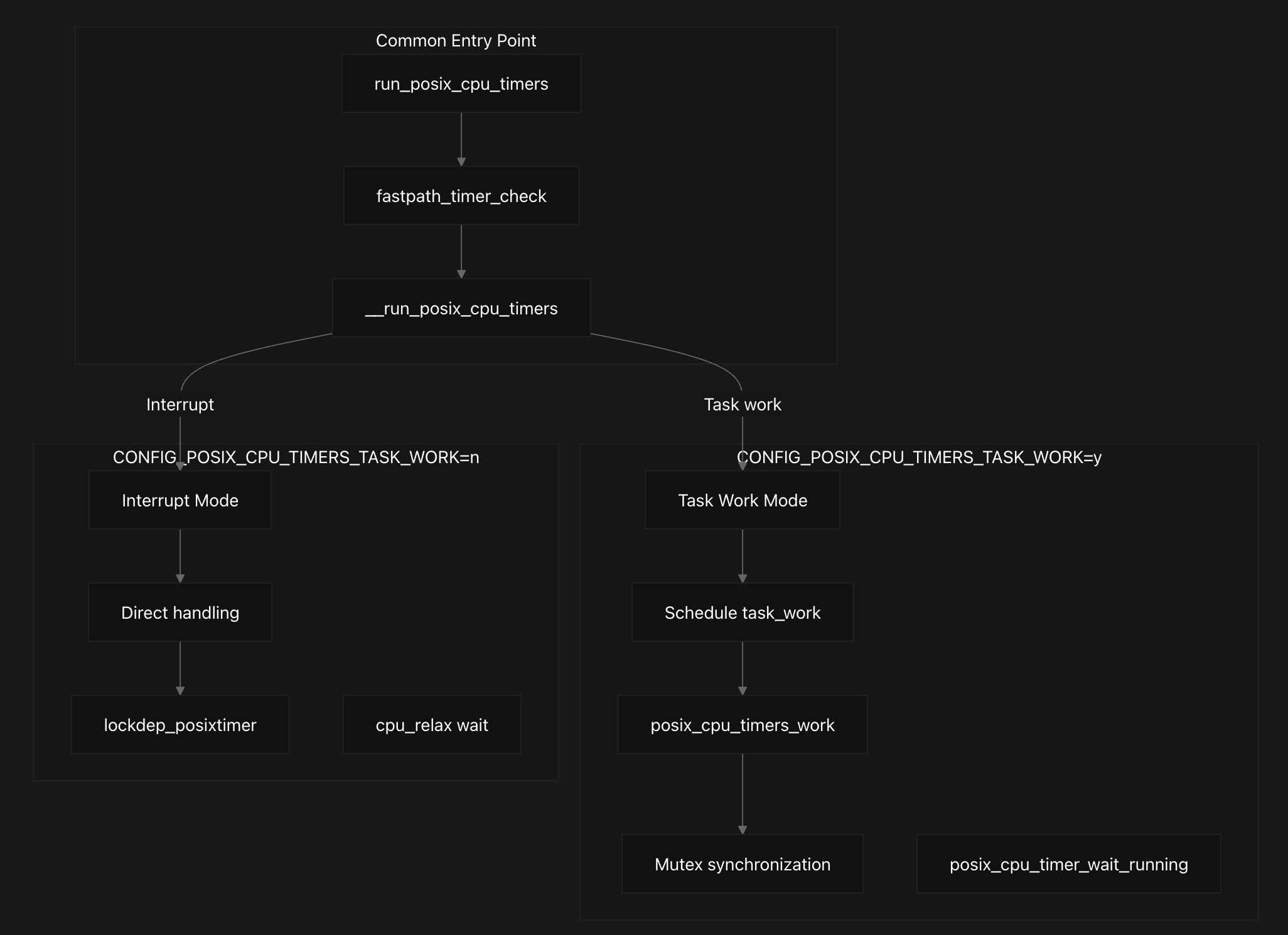

The system supports two distinct execution contexts for timer expiry processing, controlled by the CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK kernel build configuration option. In task work mode, timer expiry is deferred to process context using the task work infrastructure, allowing for more complex processing without interrupt context restrictions. In interrupt mode, timers are processed directly in interrupt context with appropriate lockdep annotations. We’ll be focusing a lot on this part later since this area of the code is where the vulnerability lies.

Clock Interface and API Integration

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

const struct k_clock clock_posix_cpu = {

.clock_getres = posix_cpu_clock_getres,

.clock_set = posix_cpu_clock_set,

.clock_get_timespec = posix_cpu_clock_get,

.timer_create = posix_cpu_timer_create,

.nsleep = posix_cpu_nsleep,

.timer_set = posix_cpu_timer_set,

.timer_del = posix_cpu_timer_del,

.timer_get = posix_cpu_timer_get,

.timer_rearm = posix_cpu_timer_rearm,

.timer_wait_running = posix_cpu_timer_wait_running,

};

...

...

static int

posix_cpu_clock_getres(const clockid_t which_clock, struct timespec64 *tp)

{

int error = validate_clock_permissions(which_clock);

if (!error) {

tp->tv_sec = 0;

tp->tv_nsec = ((NSEC_PER_SEC + HZ - 1) / HZ);

if (CPUCLOCK_WHICH(which_clock) == CPUCLOCK_SCHED) {

tp->tv_nsec = 1;

}

}

return error;

}

...

...

static int

posix_cpu_clock_set(const clockid_t clock, const struct timespec64 *tp)

{

int error = validate_clock_permissions(clock);

return error ? : -EPERM;

}

The CPU timer system exposes its functionality through a well-defined clock interface structure, providing consistent APIs for different timer operations. The clock_posix_cpu structure defines function pointers for all standard timer operations, from creation and configuration to deletion and querying. Clock resolution queries return different values depending on the clock type, with scheduler clocks providing nanosecond precision while other types are limited by the system’s timer tick frequency. Importantly, CPU clocks cannot be set, always returning EPERM to maintain system integrity.

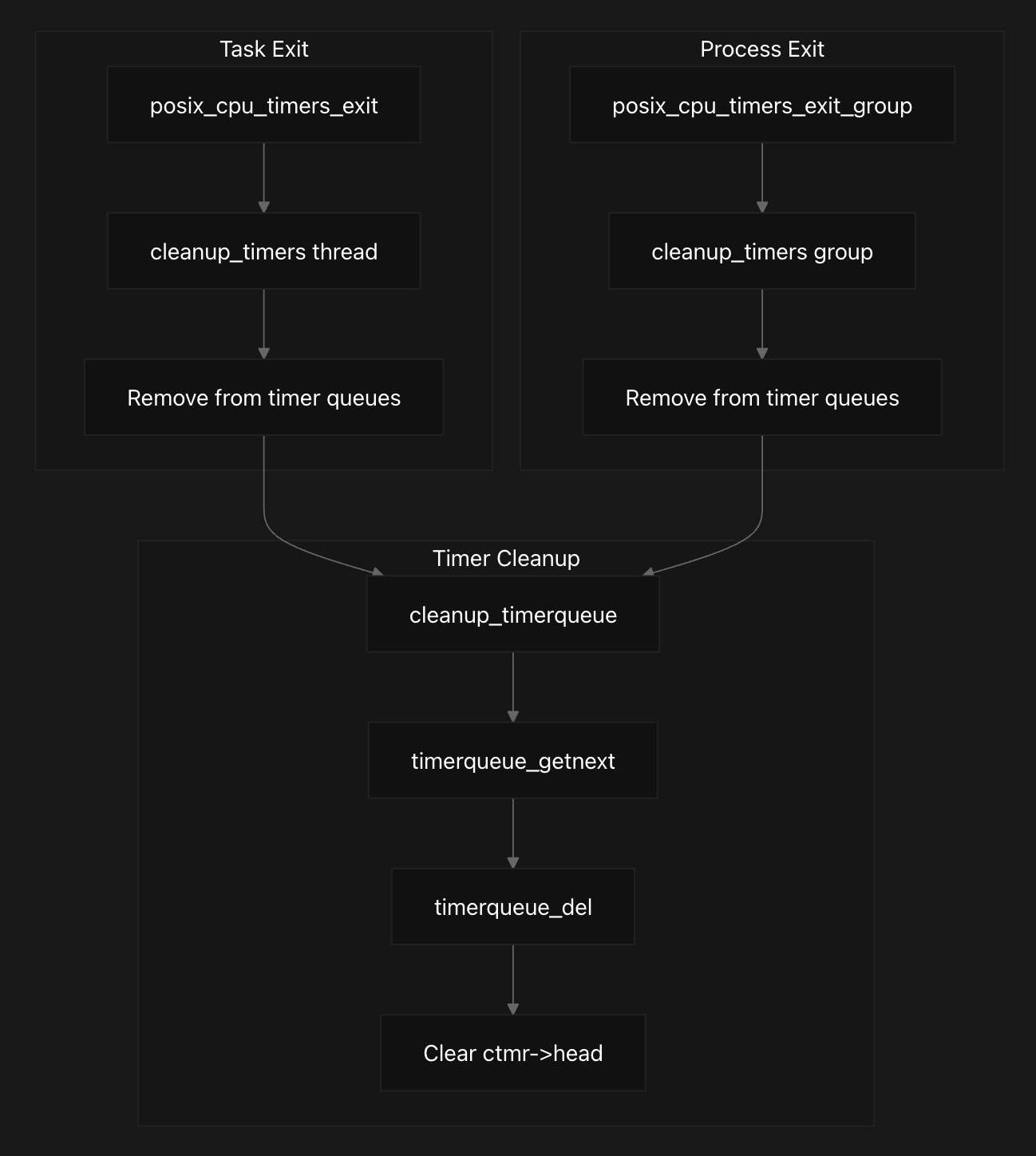

Cleanup and Process Exit Handling

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

static void cleanup_timerqueue(struct timerqueue_head *head)

{

struct timerqueue_node *node;

struct cpu_timer *ctmr;

while ((node = timerqueue_getnext(head))) {

timerqueue_del(head, node);

ctmr = container_of(node, struct cpu_timer, node);

ctmr->head = NULL;

}

}

...

...

void posix_cpu_timers_exit(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

cleanup_timers(&tsk->posix_cputimers);

}

void posix_cpu_timers_exit_group(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

cleanup_timers(&tsk->signal->posix_cputimers);

}

When processes or threads terminate, the system must carefully clean up any remaining CPU timers to prevent resource leaks and dangling references. The cleanup process removes timers from their queues and clears internal references, but leaves the timer structures accessible for any remaining user-space references. This careful approach prevents crashes while ensuring proper resource management during process termination.

Okay, now that we have some context on how this subsystem works, let’s look at the patch now.

Patch Analysis

We can access the patch via this link. It’s quite informative in nature, hence it’s easier for us to understand.

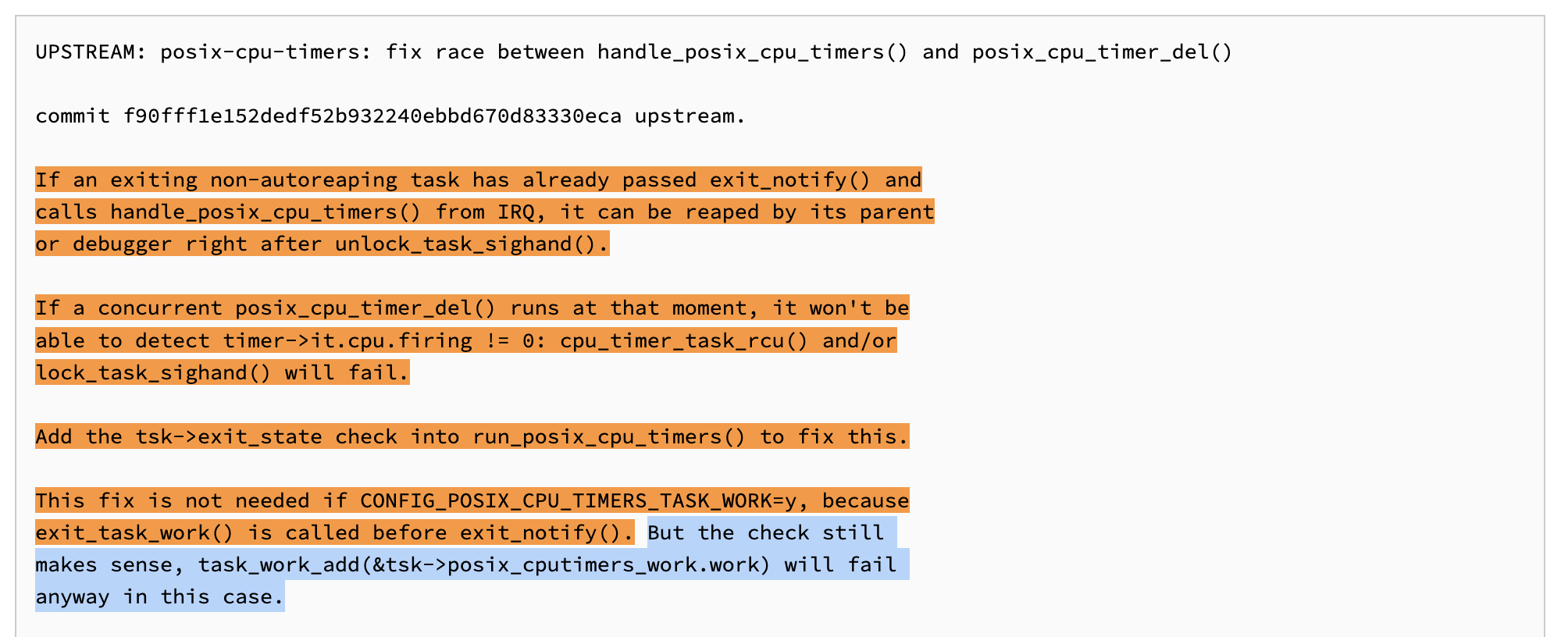

As per the patch report, the vulnerability arises when an exiting task invokes handle_posix_cpu_timers from an interrupt context while, at the same time, another thread attempts to delete a timer using posix_cpu_timer_del. This overlap creates a narrow but critical race condition. Let’s see where exactly.

There are two scenarios to this bug (as highlighted in the patch). There are 2 separate code paths (as we saw earlier) taken by run_posix_cpu_timers dependent on the CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK config flag. It can be clearly seen in the code -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

void run_posix_cpu_timers(void)

{

...

...

__run_posix_cpu_timers(tsk); // Function of Interest

}

...

...

#ifdef CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK

...

...

static inline void __run_posix_cpu_timers(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

if (WARN_ON_ONCE(tsk->posix_cputimers_work.scheduled))

return;

/* Schedule task work to actually expire the timers */

tsk->posix_cputimers_work.scheduled = true;

task_work_add(tsk, &tsk->posix_cputimers_work.work, TWA_RESUME); // First Code Path

}

...

...

#else /* CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK */

static inline void __run_posix_cpu_timers(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

lockdep_posixtimer_enter();

handle_posix_cpu_timers(tsk); // Second Code Path

lockdep_posixtimer_exit();

}

...

...

#endif /* CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK */

The specific race window occurs in brief as follows: An exiting non-autoreaping task passes through exit_notify and enters handle_posix_cpu_timers from IRQ context. Immediately afterward, the task can be reaped by its parent or a debugger right after unlock_task_sighand. If, at that same moment, a concurrent posix_cpu_timer_del executes, it may fail to detect that timer->it.cpu.firing != 0 because cpu_timer_task_rcu and/or lock_task_sighand will return failure.

According to the fix, this issue does not arise when CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK Kernel Build config (First Code Path) is enabled, since exit_task_work is guaranteed to run before exit_notify. Nevertheless, the added safeguard is still useful, because task_work_add would fail in the exit state regardless.

The fix introduces an tsk->exit_state check in run_posix_cpu_timers to close the race window:

1

2

if (tsk->exit_state)

return;

This ensures that release_task cannot proceed while handle_posix_cpu_timers is active. As a result, any concurrent call to posix_cpu_timer_del will not miss the if (timer->it.cpu.firing) condition. By moving the check to a point before any assumptions about task validity, the race is eliminated entirely.

Alright, after analyzing the patch and it’s related functions, it’s starting to come together. Let’s dive into how the bug manifests at the code level and walk through the different code paths it takes.

Vulnerable Code Analysis

As we’ve seen until now, in simple words this vulnerability stems from a timing issue that arises when two events happen almost simultaneously during task exit, allowing a critical safety check to be bypassed. The bug plays out in the interaction between timer expiry handling and timer deletion.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

/*

* Called from the timer interrupt handler to charge one tick to the current

* process. user_tick is 1 if the tick is user time, 0 for system.

*/

void update_process_times(int user_tick) // [1]

{

struct task_struct *p = current;

/* Note: this timer irq context must be accounted for as well. */

account_process_tick(p, user_tick);

run_local_timers();

rcu_sched_clock_irq(user_tick);

#ifdef CONFIG_IRQ_WORK

if (in_irq())

irq_work_tick();

#endif

scheduler_tick();

if (IS_ENABLED(CONFIG_POSIX_TIMERS))

run_posix_cpu_timers(); // [2]

}

...

...

/*

* This is called from the timer interrupt handler. The irq handler has

* already updated our counts. We need to check if any timers fire now.

* Interrupts are disabled.

*/

void run_posix_cpu_timers(void)

{

struct task_struct *tsk = current;

lockdep_assert_irqs_disabled();

if (posix_cpu_timers_work_scheduled(tsk))

return;

if (!fastpath_timer_check(tsk))

return;

__run_posix_cpu_timers(tsk); // [3]

}

...

...

#ifdef CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK

static void posix_cpu_timers_work(struct callback_head *work)

{

struct posix_cputimers_work *cw = container_of(work, typeof(*cw), work);

mutex_lock(&cw->mutex);

handle_posix_cpu_timers(current); // [4]

mutex_unlock(&cw->mutex);

}

...

...

#else /* CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK */

static inline void __run_posix_cpu_timers(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

lockdep_posixtimer_enter();

handle_posix_cpu_timers(tsk); // [4]

lockdep_posixtimer_exit();

}

The sequence begins when a Thread A fires a timer interrupt. In response, the kernel invokes update_process_times [1], which eventually calls run_posix_cpu_timers [2]. If expired timers are detected, run_posix_cpu_timers proceeds to call handle_posix_cpu_timers eventually [4] to process them. This assumes that the flag CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK is turned off. If the flag is turned on, then the code path first goes through posix_cpu_timers_work, and then continues with handle_posix_cpu_timers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

static void handle_posix_cpu_timers(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

struct k_itimer *timer, *next;

unsigned long flags, start;

LIST_HEAD(firing);

if (!lock_task_sighand(tsk, &flags)) // [5]

return;

do {

start = READ_ONCE(jiffies);

barrier();

check_thread_timers(tsk, &firing); // [6]

check_process_timers(tsk, &firing);

} while (!posix_cpu_timers_enable_work(tsk, start));

unlock_task_sighand(tsk, &flags); // [10]

list_for_each_entry_safe(timer, next, &firing, it.cpu.elist) { // [9]

int cpu_firing;

spin_lock(&timer->it_lock);

list_del_init(&timer->it.cpu.elist);

cpu_firing = timer->it.cpu.firing;

timer->it.cpu.firing = 0;

if (likely(cpu_firing >= 0))

cpu_timer_fire(timer); // [15]

rcu_assign_pointer(timer->it.cpu.handling, NULL);

spin_unlock(&timer->it_lock);

}

}

...

static void check_thread_timers(struct task_struct *tsk,

struct list_head *firing)

{

...

collect_posix_cputimers(pct, samples, firing);

...

}

...

static void check_process_timers(struct task_struct *tsk,

struct list_head *firing)

{

...

collect_posix_cputimers(pct, samples, firing);

...

}

...

static void collect_posix_cputimers(struct posix_cputimers *pct, u64 *samples,

struct list_head *firing)

{

struct posix_cputimer_base *base = pct->bases;

int i;

for (i = 0; i < CPUCLOCK_MAX; i++, base++) {

base->nextevt = collect_timerqueue(&base->tqhead, firing, // [7]

samples[i]);

}

}

...

...

#define MAX_COLLECTED 20

static u64 collect_timerqueue(struct timerqueue_head *head,

struct list_head *firing, u64 now)

{

struct timerqueue_node *next;

int i = 0;

while ((next = timerqueue_getnext(head))) {

struct cpu_timer *ctmr;

u64 expires;

ctmr = container_of(next, struct cpu_timer, node);

expires = cpu_timer_getexpires(ctmr);

if (++i == MAX_COLLECTED || now < expires)

return expires;

ctmr->firing = 1; // [8]

rcu_assign_pointer(ctmr->handling, current);

cpu_timer_dequeue(ctmr);

list_add_tail(&ctmr->elist, firing);

}

return U64_MAX;

}

Inside handle_posix_cpu_timers, the kernel locks the task’s signal handler with lock_task_sighand [5]. Then, the function processes the expired timers by calling check_thread_timers and check_process_timers [6] which call collect_posix_cputimers and collect_timerqueue [7] accordingly to set the time firing by ctmr->firing = 1 [8]. After the firing flag is set, the timer is added to the firing list and later processed in the loop where timer->it.cpu.firing is accessed and reset to 0 [9] . handle_posix_cpu_timers then releases the lock with unlock_task_sighand [10].

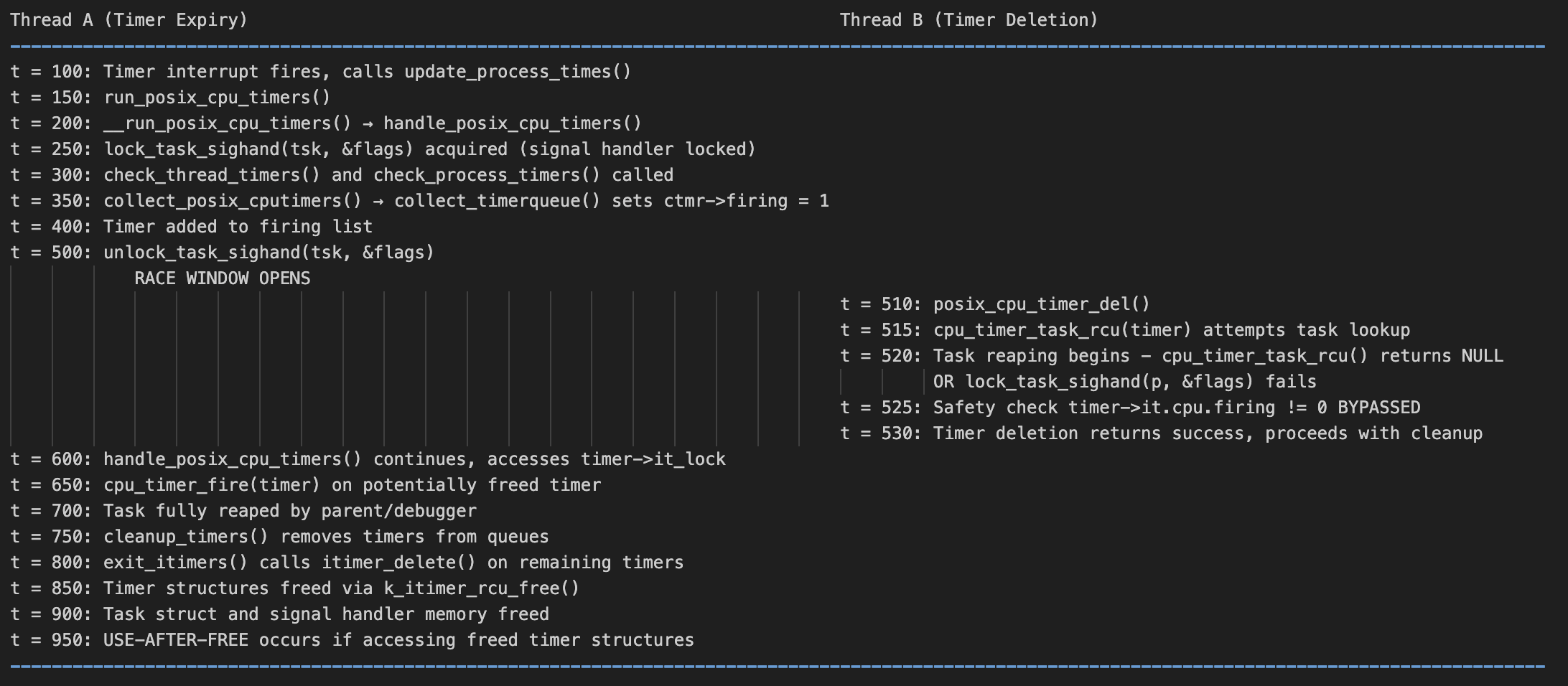

It is at this unlock point that the race condition emerges. Once the lock is released, the exiting task may be fully reaped (freed) by its parent process, invalidating its task structures. Let’s check how an another thread could be affected by this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

/*

* Clean up a CPU-clock timer that is about to be destroyed.

* This is called from timer deletion with the timer already locked.

* If we return TIMER_RETRY, it's necessary to release the timer's lock

* and try again. (This happens when the timer is in the middle of firing.)

*/

static int posix_cpu_timer_del(struct k_itimer *timer) // [11]

{

struct cpu_timer *ctmr = &timer->it.cpu;

struct sighand_struct *sighand;

struct task_struct *p;

unsigned long flags;

int ret = 0;

rcu_read_lock();

p = cpu_timer_task_rcu(timer); // [12]

if (!p)

goto out;

/*

* Protect against sighand release/switch in exit/exec and process/

* thread timer list entry concurrent read/writes.

*/

sighand = lock_task_sighand(p, &flags); // [13]

if (unlikely(sighand == NULL)) {

/*

* This raced with the reaping of the task. The exit cleanup

* should have removed this timer from the timer queue.

*/

WARN_ON_ONCE(ctmr->head || timerqueue_node_queued(&ctmr->node));

} else {

if (timer->it.cpu.firing) // [14]

ret = TIMER_RETRY;

else

disarm_timer(timer, p);

unlock_task_sighand(p, &flags);

}

out:

rcu_read_unlock();

if (!ret)

put_pid(ctmr->pid);

return ret;

}

Another thread, let’s say, Thread B may attempt to delete a timer by calling posix_cpu_timer_del [11] . This deletion path relies on several steps: it looks up the task with cpu_timer_task_rcu [12], acquires the signal handler lock via lock_task_sighand [13] , and finally checks whether timer->it.cpu.firing != 0 [14] to determine if the timer is currently active.

The problem arises if the task is reaped in the tiny window between handle_posix_cpu_timers unlocking the signal handler and posix_cpu_timer_del performing its checks. In such a case, cpu_timer_task_rcu may return NULL because the task no longer exists, or lock_task_sighand may fail because the signal handler has already been freed. Either outcome prevents the deleter from reaching the critical check of timer->it.cpu.firing != 0. As a result, the deleter assumes the timer is safe to remove—even though another thread (Thread A) is still processing it.

This mis-synchronization leads to a classic Time-of-Check to Time-of-Use (TOCTOU) bug where the “check” and “use” operations are separated by a critical race window. The Time of Check (TOC) occurs in posix_cpu_timer_del when it attempts to verify if a timer is currently firing through a three-step sequence as we discussed above: first calling cpu_timer_task_rcu(timer) to check if the task exists, then attempting to acquire the sighand lock via lock_task_sighand(p, &flags), and finally checking the timer->it.cpu.firing flag to determine if the timer is currently active.

The Time of Use (TOU) happens in handle_posix_cpu_timers when it processes the firing timer after releasing the sighand lock. This use sequence involves setting ctmr->firing = 1 in while holding the lock (which occurs in collect_timerqueue as we saw earlier), releasing the sighand lock, and then continuing to use the timer in the firing loop where it accesses timer->it_lock and calls cpu_timer_fire(timer) [15].

Here’s a timeline with the events we have discussed -

When this race succeeds, timer deletion completes without detecting the firing state while Thread A continues execution with dangling pointers to freed timer structures, leading to use-after-free conditions when Thread A accesses timer->it_lock, timer->it.cpu.elist, or calls cpu_timer_fire on potentially freed memory. This can result in kernel crashes from accessing freed memory, memory corruption if the freed memory gets reallocated, or even privilege escalation if an attacker can control the freed memory contents, making this TOCTOU vulnerability particularly dangerous because the synchronization mechanism (sighand lock) itself becomes invalid during task reaping.

Creating the Test Environment

To develop a testing environment for the vulnerability, I created an Android Kernel Emulation Setup with Debugging Support. We’ll be pulling the tag 1bf1aa362e6b9573a310fcd14f35bc875b42ba83 from the Android Kernel Common Repository. The patch-diff or the fix needs to be reverted (or commented) in kernel/time/posix-cpu-timers.c to reintroduce the vulnerability in the environment for testing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

void run_posix_cpu_timers(void)

{

struct task_struct *tsk = current;

lockdep_assert_irqs_disabled();

/*

* Ensure that release_task(tsk) can't happen while

* handle_posix_cpu_timers() is running. Otherwise, a concurrent

* posix_cpu_timer_del() may fail to lock_task_sighand(tsk) and

* miss timer->it.cpu.firing != 0.

*/

// COMMENT OUT THE FIX

// if (tsk->exit_state)

// return;

...

}

We’ll now run the following commands to setup the Android Kernel Emulation Environment.

1

2

3

4

mkdir android-kernel

cd android-kernel

wget https://android.googlesource.com/kernel/common/+archive/1bf1aa362e6b9573a310fcd14f35bc875b42ba83.tar.gz

tar xf 1bf1aa362e6b9573a310fcd14f35bc875b42ba83.tar.gz

The next steps largely follow the compilation steps from my earlier blog, but with an important caveat. As noted in the patch, the behavior of the vulnerable code path depends on the CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK flag in the generated kernel config (.config). To properly analyze this, we need two builds: one with the flag enabled and one with it disabled.

Compiling with the flag enabled was straightforward, but I ran into issues when trying to set it to n. Even when forced, the kernel build system automatically flips it back to y. To work around this, I manually patched the relevant functions (shown below) to the ones above before compiling the kernel.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

#else /* CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK */

static inline void __run_posix_cpu_timers(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

lockdep_posixtimer_enter();

handle_posix_cpu_timers(tsk); // Code Path that we are interested in

lockdep_posixtimer_exit();

}

static void posix_cpu_timer_wait_running(struct k_itimer *timr)

{

cpu_relax();

}

static void posix_cpu_timer_wait_running_nsleep(struct k_itimer *timr)

{

spin_unlock_irq(&timr->it_lock);

cpu_relax();

spin_lock_irq(&timr->it_lock);

}

static inline bool posix_cpu_timers_work_scheduled(struct task_struct *tsk)

{

return false;

}

static inline bool posix_cpu_timers_enable_work(struct task_struct *tsk,

unsigned long start)

{

return true;

}

#endif /* CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK */

Triggering the Bug

Since I cannot share the exact steps used to reproduce the bug (as noted in the disclaimer), it should still be clear from our discussion that the Race Condition can be triggered when one thread forces a timer interrupt to invoke run_posix_cpu_timers, while another thread concurrently calls posix_cpu_timer_del.

We need to target the timing window where handle_posix_cpu_timers releases the signal handler lock. At that precise moment, the exiting task may be fully cleaned up, freeing its task_struct and associated resources. If posix_cpu_timer_del executes during this window, it may miss the timer firing check leading to failure of cpu_timer_task_rcu or lock_task_sighand calls. At that point the kernel becomes unstable and may result in a crash or undefined behavior.

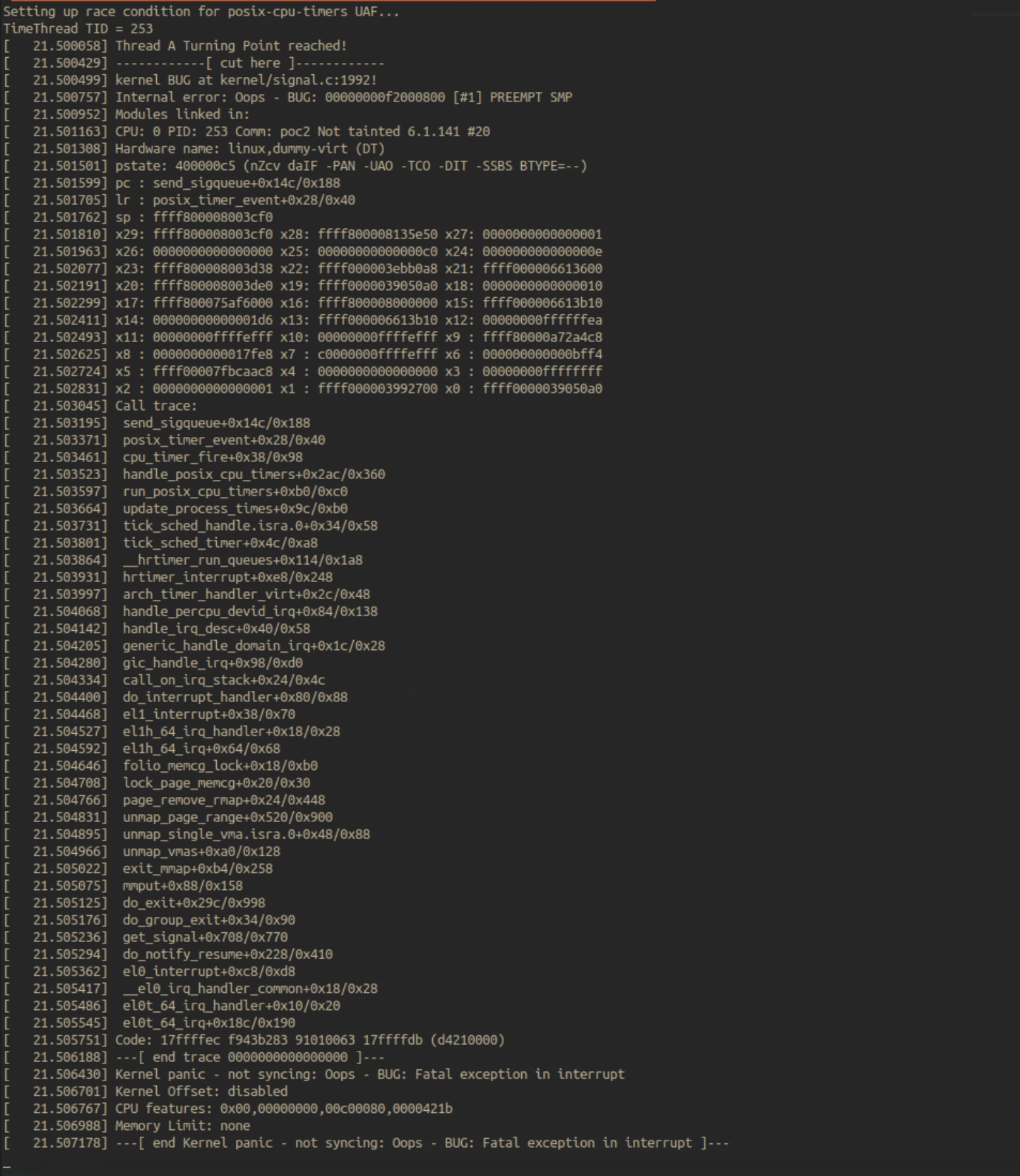

Based on the knowledge we gathered so far, I developed a minimal trigger PoC for demonstration purposes to be tested out in our emulated environment. I decided to first test the PoC on the CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK=n setting on which the patch emphasises on, and upon doing so, after a few tries, we get a beautiful crash -

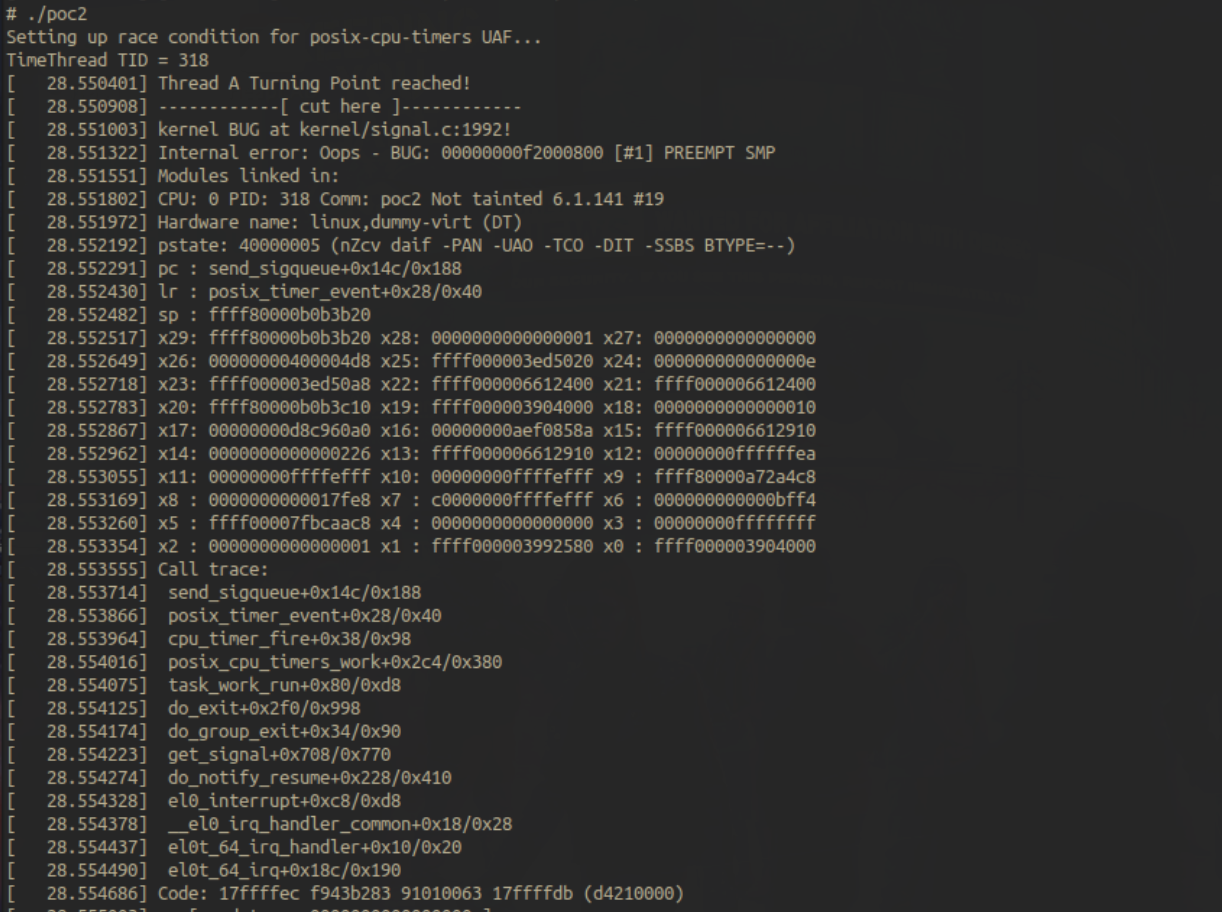

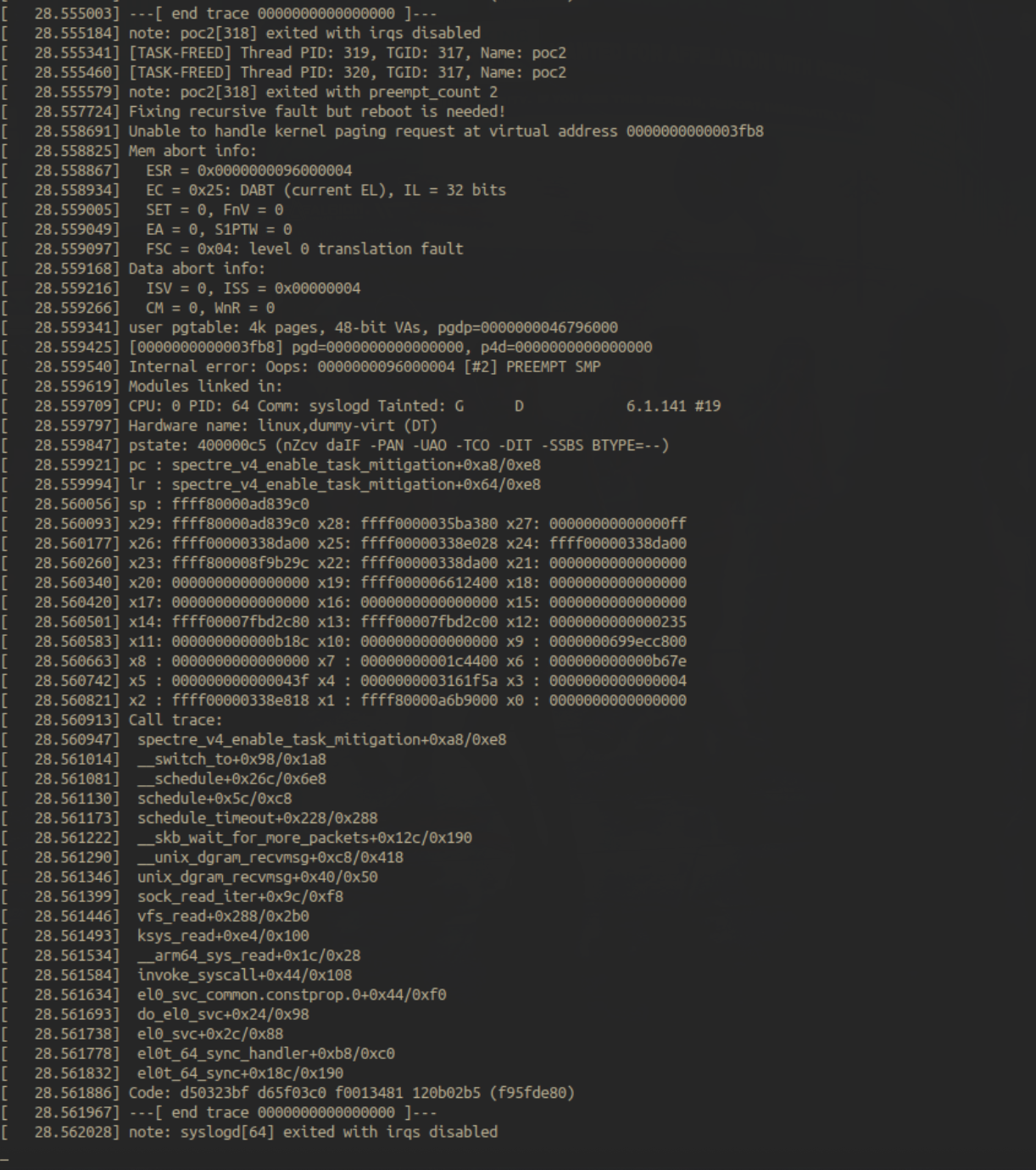

After the poc worked on the above scenario, I was intrigued to try it out in the default settings CONFIG_POSIX_CPU_TIMERS_TASK_WORK=y as mentioned in the last part of the patch, and upon doing so, after a few tries, we again get a kernel crash -

Conclusion

The investigation into CVE-2025-38352 highlights how subtle race conditions in kernel subsystems like posix-cpu-timers can lead to stability and security concerns, especially in environments such as Android. By analyzing the patch, studying the vulnerable behavior, and safely demonstrating its impact with a controlled crash scenario, my goal was to shed light on the underlying vulnerability mechanics and patch-fix analysis. Ultimately, the fix not only addresses a potential exploitation path but also strengthens the overall reliability of the Linux timekeeping infrastructure. Overall, a fun project for me.

Credits

Hey There! If you’ve come across any bugs or have ideas for improvements, feel free to reach out to me on X! If your suggestion proves helpful and gets implemented, I’ll gladly credit you in this dedicated Credits section. Thanks for reading!